From seamless automation with REST APIs to robust tools for DNS record control, custom DNS services make simpler how websites are managed and maintained.

Default DNS Management Simplified

When you buy a domain from places like Google Domains, handling your DNS records is done right there. It’s easy for many folks, but it has its limits. For example, there’s no fancy tool like a REST API for managing your domains. This means you can’t automate tasks such as creating subdomains using scripts or smoothly deploying projects from your command line.

Imagine a scenario where you want a new subdomain every time you start a new project. Sadly, with the basic DNS management provided by default, that’s not possible.

Custom DNS Management: A Better Option

The world of DNS management isn’t just limited to what domain registrars offer. There are third-party services like Cloudflare DNS, Amazon Route 53, or DNSimple. These services bring in a lot more flexibility and tools for managing your DNS records.

One great thing about these custom DNS services is that they come with REST APIs. This means developers can talk to their DNS settings using code, opening up a whole new world of automation. Imagine making a simple request to create a new subdomain or updating your DNS records automatically when your infrastructure changes. That’s the power custom DNS management offers.

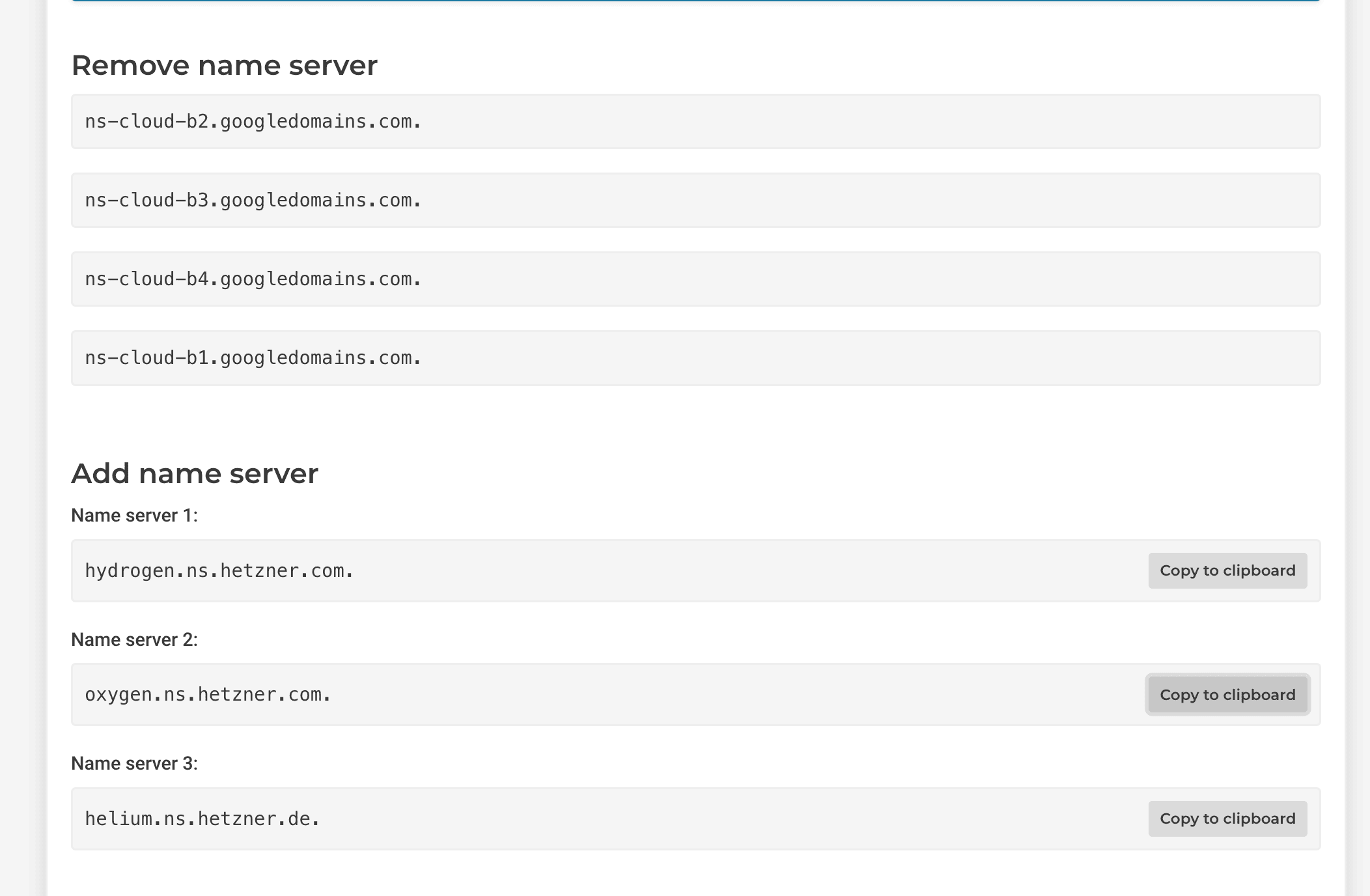

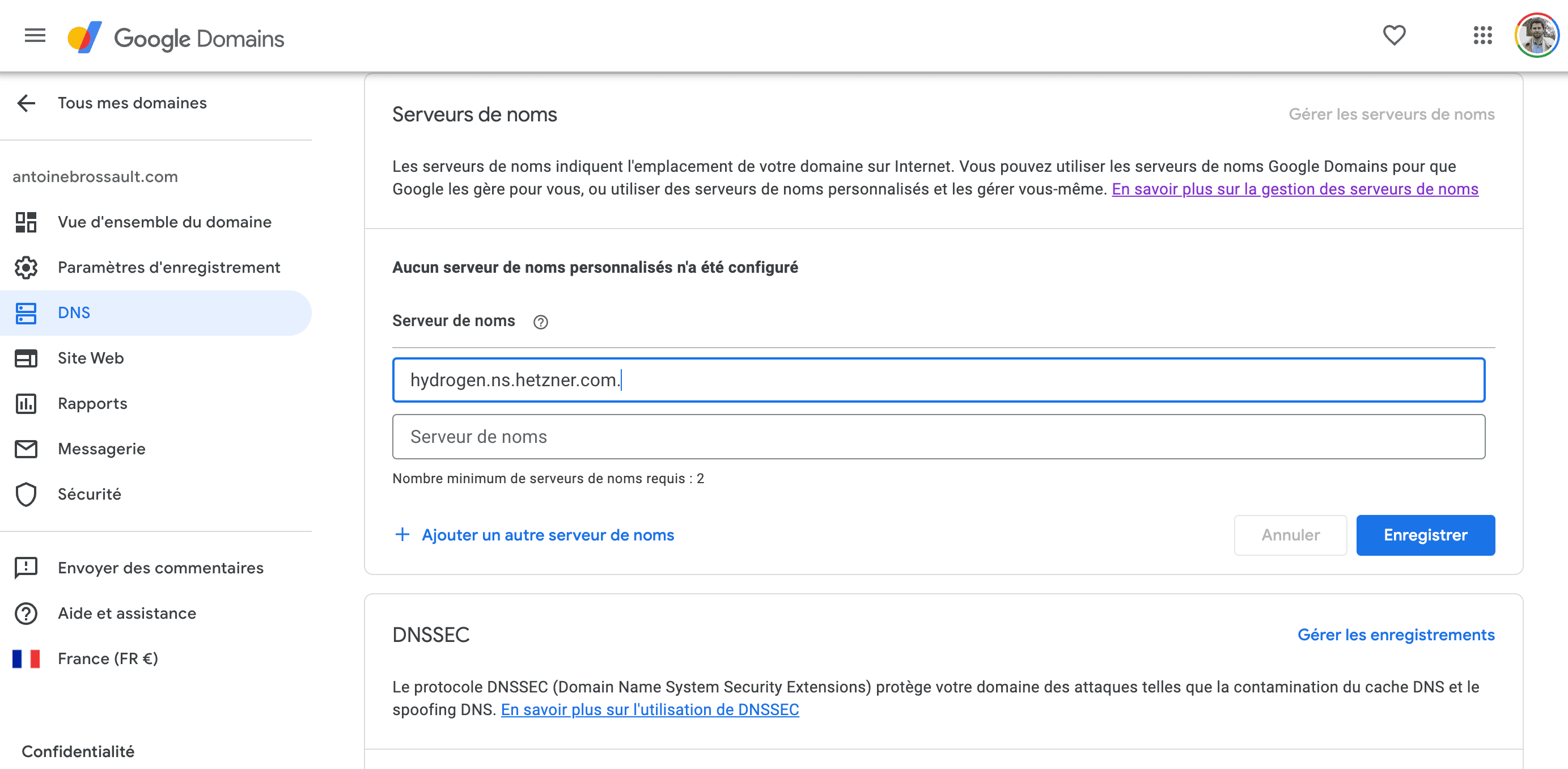

Moving your Name server

If you want to switch to a custom DNS service, you’ll need to redirect your domain’s DNS queries from your registrar’s default servers to the servers of your chosen DNS provider.

In my situation, I decided to have Hetzner handle my DNS, but my domain is currently looked after by Google.

To make this change, I had to update the name servers, following the instructions provided in the screenshots.

Hetzner new server name :

Google domain registrar :

How to create a record with the Hetzner API

Here’s a small script to get the zones and to create a new record.

The api key is store in a .env. file at the root of my project.

You need to install dotenv and axios

npm install dotenv

npm install axios

touch .env

The .env file looks like this :

hetznerDNSToken = sbfwolkdnazhdhl9833

The script :

const dotenv = require('dotenv');

dotenv.config();

const axios = require('axios');

const axiosConfig = {

headers: {

'Auth-API-Token': process.env.hetznerDNSToken

}

}

/**

* Retrieves all DNS zones from Hetzner DNS API.

* @async

* @returns {Promise<Array>} An array containing information about all DNS zones.

* @throws {Error} If an error occurs during the fetch process or if no zones are found.

*/

const getZones = async () => {

const response = await axios.get('https://dns.hetzner.com/api/v1/zones', axiosConfig);

if(!response.data) throw new Error('Error fetching zones:', response.data);

const {zones} = response.data;

if(!zones) throw new Error('No zones found');

return zones;

};

/**

* Retrieves all records associated with a specific DNS zone from Hetzner DNS API.

* @async

* @param {string} zoneId - The ID of the DNS zone to retrieve records from.

* @returns {Promise<Object>} An object containing information about DNS records.

* @throws {Error} If an error occurs during the fetch process.

*/

const getRecords = async (zoneId) => {

const response = await axios.get(`https://dns.hetzner.com/api/v1/records?zone_id=${zoneId}`, axiosConfig);

if(!response.data) throw new Error('Error fetching records:', response.data);

return response.data;

};

/**

* Creates a DNS record within a specific DNS zone using the provided data.

* @async

* @param {object} requestData - An object containing data required to create a DNS record.

* @param {string} requestData.value - The value of the DNS record.

* @param {number} requestData.ttl - The Time-To-Live (TTL) of the DNS record.

* @param {string} requestData.type - The type of the DNS record (e.g., 'A', 'CNAME', 'MX').

* @param {string} requestData.name - The name of the DNS record.

* @param {string} requestData.zone_id - The ID of the DNS zone where the record will be created.

* @returns {Promise<Object>} An object containing information about the created DNS record.

* @throws {Error} If any required property is missing or if an error occurs during the creation process.

*/

const createRecord = async (requestData) => {

const requiredProperties = ['value', 'ttl', 'type', 'name', 'zone_id'];

for (const prop of requiredProperties) {

if (!(prop in requestData)) {

throw new Error(`Missing required property: ${prop}`);

}

}

const response = await axios.post('https://dns.hetzner.com/api/v1/records', requestData, axiosConfig);

return response.data;

};

(async () => {

const zones = await getZones();

console.log(zones);

const records = await getRecords(zones[0].id);

console.log(records);

const response = await createRecord({

zone_id: zones[0].id,

ttl: 86400,

name: 'testa',

type: 'A',

value: '51.68.227.24'

});

console.log(response);

})().catch(console.log);

Test your custom DNS server with dig

dig @1.0.0.1 lancieux.antoinebrossault.com. AAAA

This command is like asking a specific phone book (the DNS server at 1.0.0.1) for the phone number (IPv6 address) associated with a particular name (lancieux.antoinebrossault.com).

The part AAAA specifies that we’re specifically looking for an IPv6 address.

So, the command is basically saying: « Hey, DNS server at 1.0.0.1, tell me the IPv6 address for the name lancieux.antoinebrossault.com. »

Result

; <<>> DiG 9.10.6 <<>> @1.0.0.1 lancieux.antoinebrossault.com. AAAA

; (1 server found)

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 54149

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 0, AUTHORITY: 1, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 1232

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;lancieux.antoinebrossault.com. IN AAAA

;; AUTHORITY SECTION:

antoinebrossault.com. 3600 IN SOA hydrogen.ns.hetzner.com. dns.hetzner.com. 2024033004 86400 10800 3600000 3600

;; Query time: 113 msec

;; SERVER: 1.0.0.1#53(1.0.0.1)

;; WHEN: Sat Mar 30 22:28:50 CET 2024

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 118

Under the Authority section we can see our new servers

;; AUTHORITY SECTION:

antoinebrossault.com. 3600 IN SOA hydrogen.ns.hetzner.com. dns.hetzner.com. 2024033004 86400 10800 3600000 3600

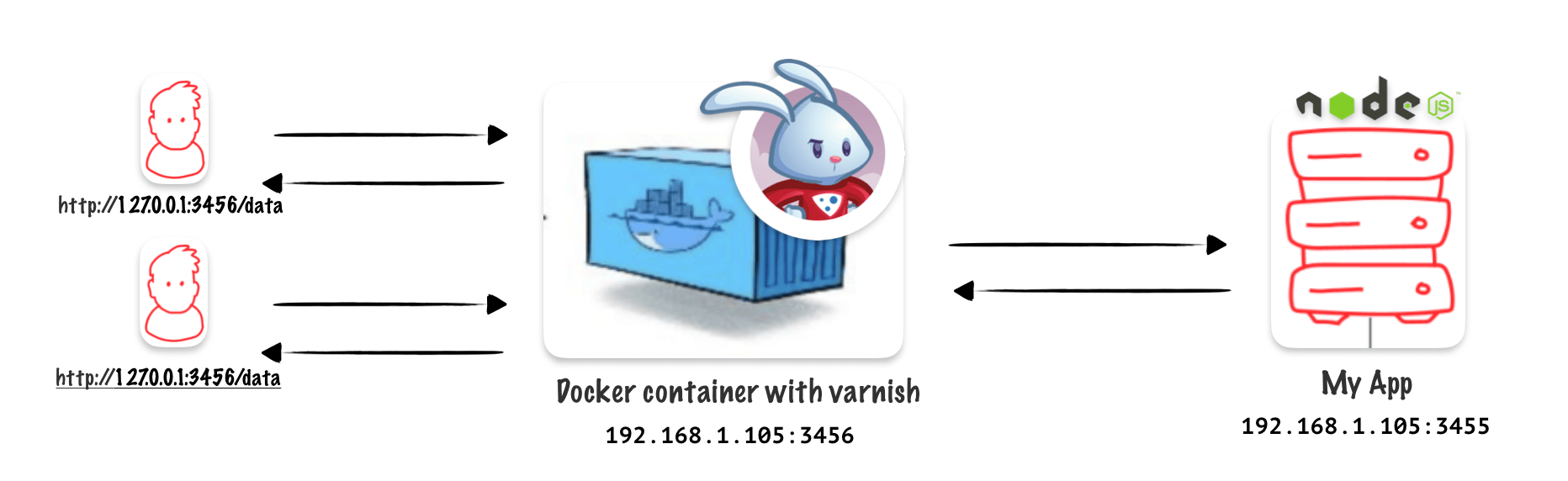

Create the docker container

docker run --name varnish -p 3456:80 varnish

This command runs a Docker container named « varnish » using the « varnish » image. It maps port 3456 on the host to port 80 in the container, allowing access to the containerized varnish service.

Start the container

docker start varnish

Find your local ip address

ifconfig | grep 192

Returns :

inet 192.168.1.105 netmask 0xffffff00 broadcast 192.168.1.255

inet 192.168.64.1 netmask 0xffffff00 broadcast 192.168.64.255

Here is the ip I will use as hostname : 192.168.1.105

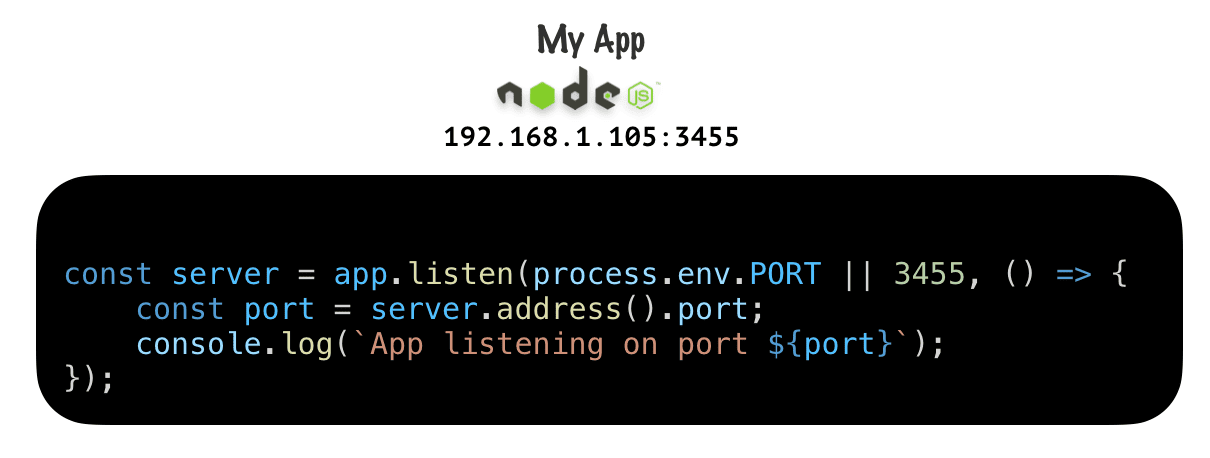

Create a default VCL

On my local machine I created : default.vcl

vcl 4.0;

backend default {

.host = "192.168.64.1";

.port = "3455";

}

The host and the port are the one from my application behind Varnish

Copy the VCL in the container

docker cp default.vcl varnish:/etc/varnish

Restart the container

docker restart varnish

Start to play with the VCL

vcl 4.0;

backend default {

.host = "192.168.64.1";

.port = "3455";

}

sub vcl_recv {

if (req.url ~ "keep-fresh") {

return (pass);

}

}

sub vcl_backend_response {

# Set a default

set beresp.ttl = 30s;

if(bereq.url ~ "data"){

set beresp.ttl = 8s;

}

}

sub vcl_deliver {

set resp.http.Antoine = "Hello";

}

Copy the custom VCL and restart in one command

docker cp default.vcl varnish:/etc/varnish && docker restart varnish

Do not cache a specific url :

sub vcl_recv {

if (req.url ~ "keep-fresh") {

return (pass);

}

}

When I call http://localhost:3456/keep-fresh it’s never cached :

abrossault@macbook ~ % curlHeaders http://localhost:3456/keep-fresh

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

X-Powered-By: Express

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Content-Length: 35

ETag: W/"23-gZVVGSUOoG7U6R/CPEAL+l/wRng"

Date: Tue, 26 Mar 2024 13:16:17 GMT

X-Varnish: 492

Age: 0

Via: 1.1 5f6b48482a6f (Varnish/7.5)

Antoine: Hello

Connection: keep-alive

Only cache an url for 8sec

sub vcl_backend_response {

# Set a default

set beresp.ttl = 30s;

if(bereq.url ~ "data"){

set beresp.ttl = 8s;

}

}

When I call http://localhost:3456/data it will remain in cache for only 8sec

abrossault@macbook ~ % curlHeaders http://localhost:3456/data

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

X-Powered-By: Express

ETag: W/"5fc7-3rbdk4/NvVpLo6VEDXT1gH26XH8"

Date: Tue, 26 Mar 2024 13:18:44 GMT

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Content-Length: 24519

X-Varnish: 98308 32836

Age: 8

Via: 1.1 5f6b48482a6f (Varnish/7.5)

Accept-Ranges: bytes

Antoine: Hello

Connection: keep-alive

Here the Age is 8 Age: 8

Then when I call this URL again the Age header is reset :

abrossault@macbook ~ % curlHeaders http://localhost:3456/data

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

X-Powered-By: Express

ETag: W/"5fc7-3rbdk4/NvVpLo6VEDXT1gH26XH8"

Date: Tue, 26 Mar 2024 13:18:53 GMT

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Content-Length: 24519

X-Varnish: 505 98309

Age: 2

Via: 1.1 5f6b48482a6f (Varnish/7.5)

Accept-Ranges: bytes

Antoine: Hello

Connection: keep-alive

Cache static assets for 7 days

All the assets finish with (css|js|png|jpg|jpeg|gif|ico|woff|woff2|svg|otf|ttf|eot) will be cached for 7 days, and we put a cache-control header

sub vcl_backend_response {

# Set a default

set beresp.ttl = 30s;

if (bereq.url ~ "\.(css|js|png|jpg|jpeg|gif|ico|woff|woff2|svg|otf|ttf|eot)$") {

set beresp.ttl = 7d; // Cache static assets for 7 days

set beresp.http.Cache-Control = "public, max-age=604800"; // Set cache-control header

}

}

As you can see after few minutes my Age header went up by more than the default ttl

abrossault@macbook ~ % curlHeaders http://localhost:3456/js/app.js

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

X-Powered-By: Express

Last-Modified: Tue, 26 Mar 2024 13:39:12 GMT

ETag: W/"15-18e7afc80c4"

Content-Type: application/javascript; charset=UTF-8

Content-Length: 21

Date: Tue, 26 Mar 2024 13:55:58 GMT

Cache-Control: public, max-age=604800

X-Varnish: 77 32771

Age: 669

Via: 1.1 5f6b48482a6f (Varnish/7.5)

Accept-Ranges: bytes

Antoine: Hello

Connection: keep-alive

Redirect a URL

sub vcl_recv {

if (req.url == "/old-url") {

return (synth(301, "/new-url")); // Redirect to new URL

}

}

And

sub vcl_synth {

if (resp.status == 301) {

set resp.http.location = resp.reason;

set resp.reason = "Moved";

return (deliver);

}

}

Result :

abrossault@macbook ~ % curlHeaders http://localhost:3456/old-url

HTTP/1.1 301 Moved

Date: Tue, 26 Mar 2024 14:42:28 GMT

Server: Varnish

X-Varnish: 32773

location: /new-url

Content-Length: 0

Connection: keep-alive

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

X-Powered-By: Express

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Content-Length: 24

ETag: W/"18-/cE9SPz52ciEALTCHs8hXDUSICk"

Date: Tue, 26 Mar 2024 14:42:28 GMT

X-Varnish: 32774

Age: 0

Via: 1.1 5f6b48482a6f (Varnish/7.5)

Accept-Ranges: bytes

Antoine: Hello

Connection: keep-alive

Purge

If I want to purge a specific URL :

First set an acl with the authorized Ips

acl purge {

"localhost";

"192.168.1.105";

"192.168.65.1";

}

sub vcl_recv {

# Purge

if (req.method == "PURGE") {

if (client.ip !~ purge) {

return (synth(405, "Method Not Allowed for : "+client.ip));

}

return (purge);

}

}

Then use this curl command to purge

curl -X PURGE http://192.168.64.1:3456/data -i

Which will return :

HTTP/1.1 200 Purged

Date: Tue, 26 Mar 2024 16:03:53 GMT

Server: Varnish

X-Varnish: 32773

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Retry-After: 5

Content-Length: 240

Connection: keep-alive

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>200 Purged</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Error 200 Purged</h1>

<p>Purged</p>

<h3>Guru Meditation:</h3>

<p>XID: 32773</p>

<hr>

<p>Varnish cache server</p>

</body>

</html>

Dynamic backend

If you want to select a backend based on an header, here’s one solution.

Here I have my two apps running on different ports : 192.168.64.1:3454 and 192.168.64.1:3455

First I define my backends :

backend backend_one {

.host = "192.168.64.1";

.port = "3454";

}

backend backend_two {

.host = "192.168.64.1";

.port = "3455";

}

backend default {

.host = "192.168.64.1";

.port = "3454";

}

Then I select the backend I want based on a header in vcl_recv, with varnish you can set the backend by using req.backend_hint as described in the documentation. Note that if you use Fastly flavored VCL you have to use set req.backend = <backendName> as described in the doc

sub vcl_recv {

if (req.http.X-Custom-Backend) {

if (req.http.X-Custom-Backend == "one") {

set req.backend_hint = backend_one;

} else if (req.http.X-Custom-Backend == "two") {

set req.backend_hint = backend_two;

} else {

# If the header is set but unrecognized, use the default

set req.backend_hint = default;

}

} else {

# If no header is present, use the default

set req.backend_hint = default;

}

}

To test it :

curl -H "X-Custom-Backend: two" http://192.168.64.1:3456/

or

curl -H "X-Custom-Backend: one" http://192.168.64.1:3456/

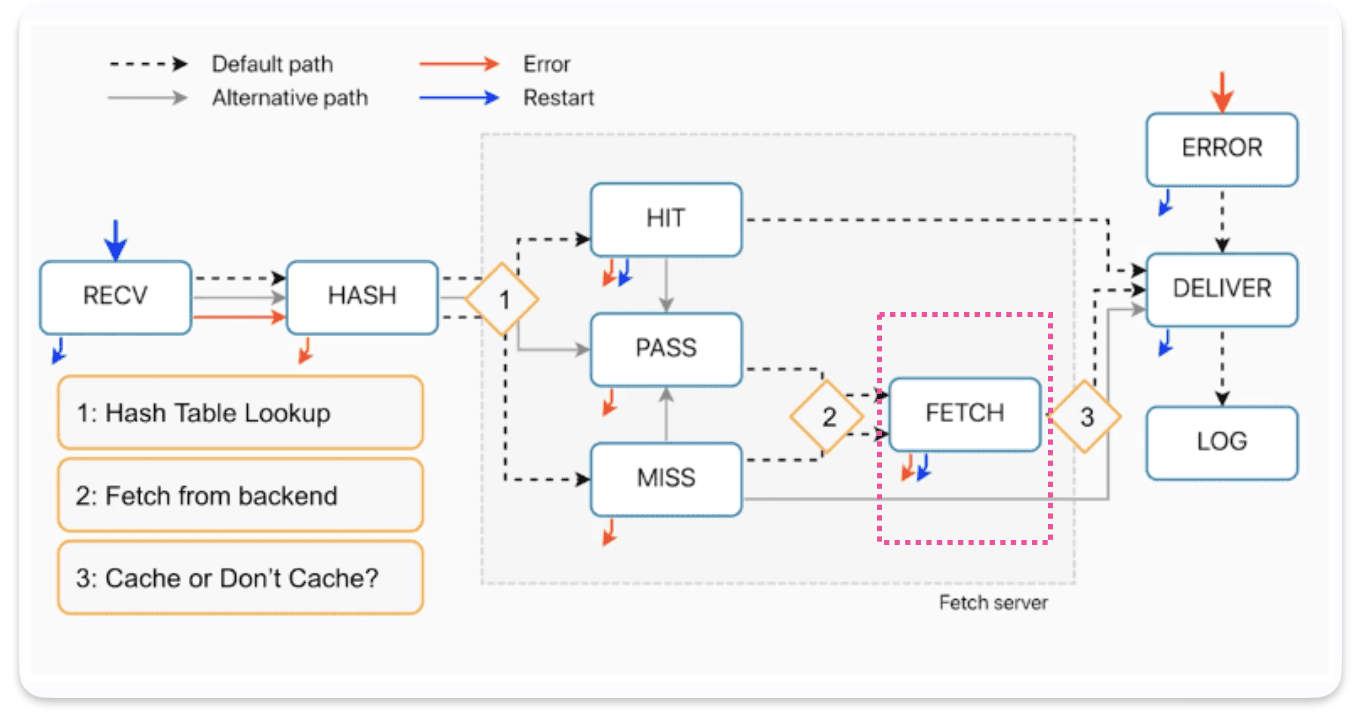

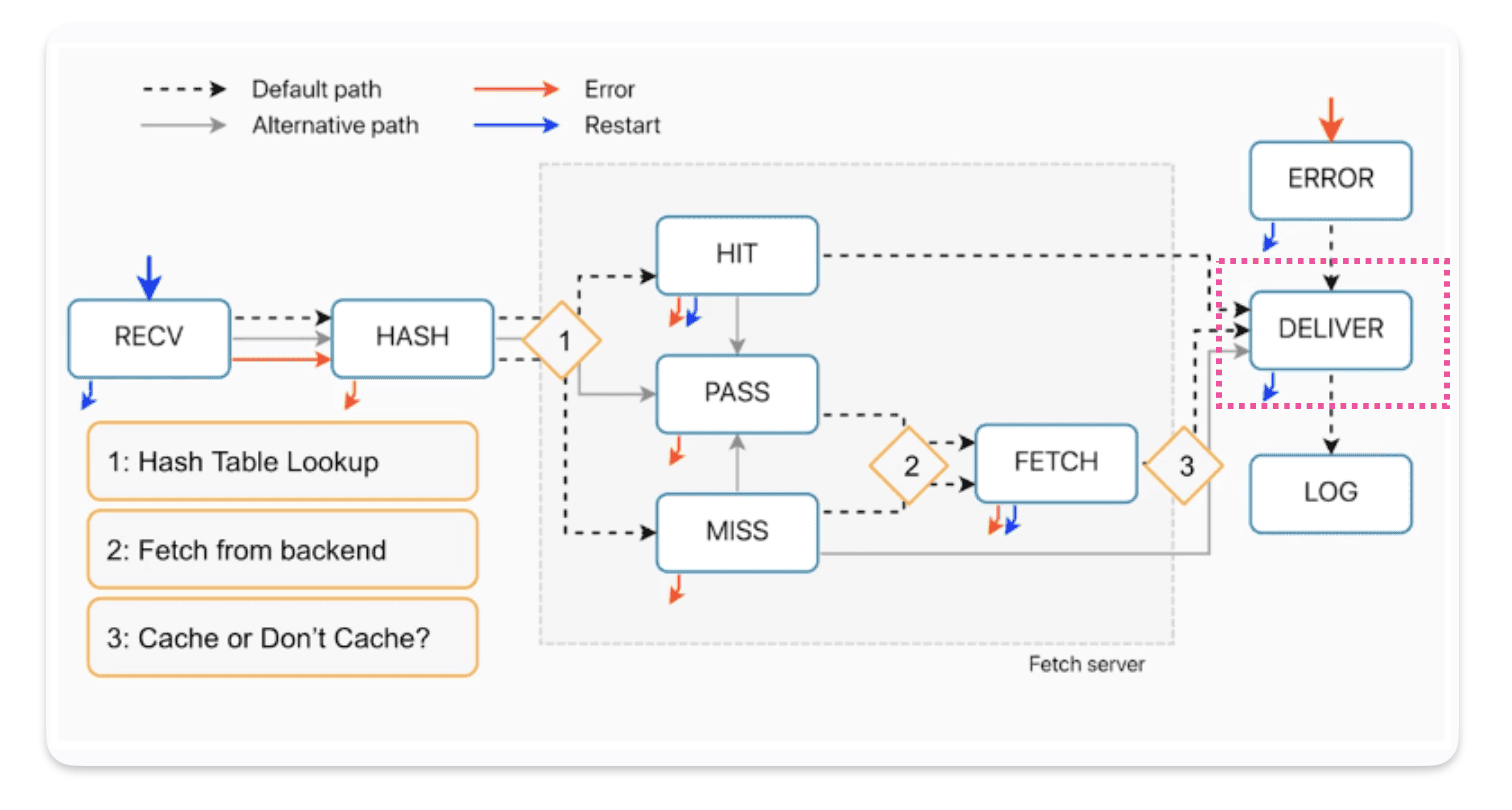

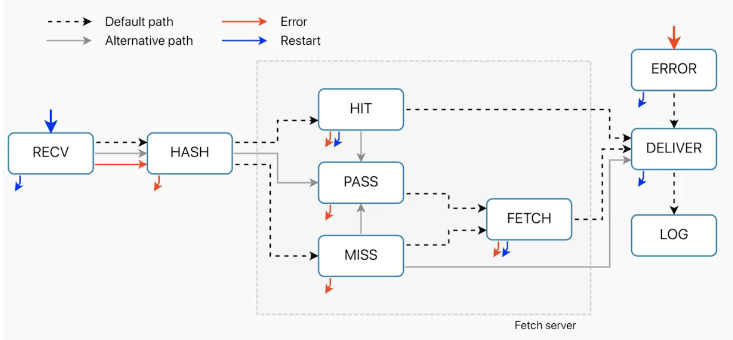

VCL_hash

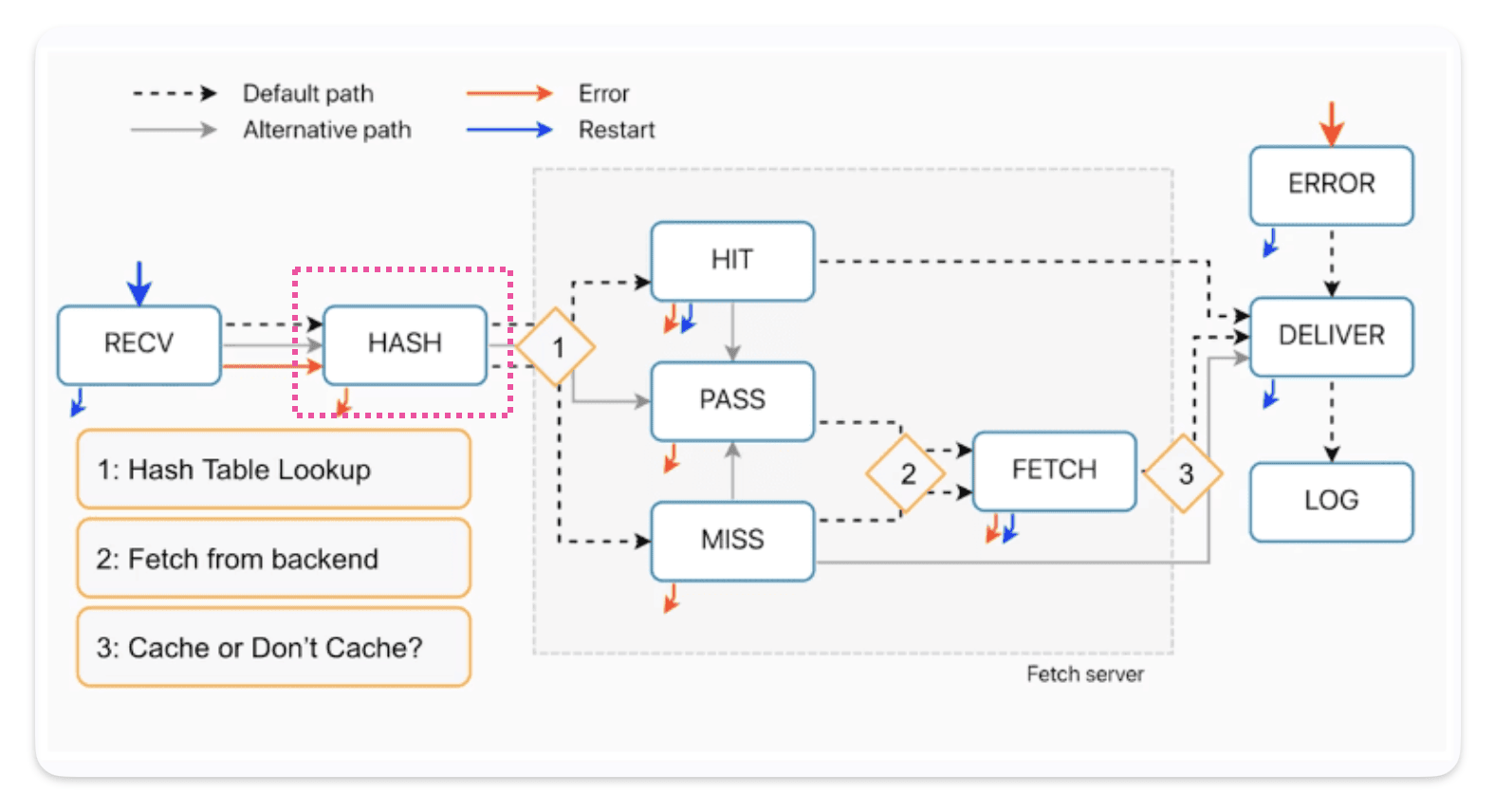

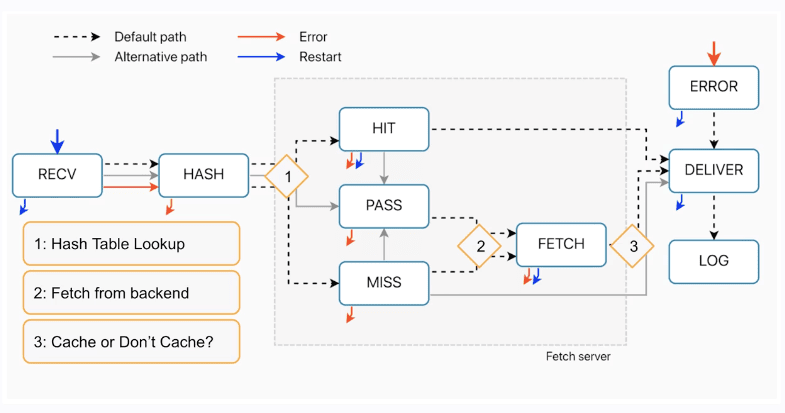

From this diagram we can see vcl_hash runs after receive and there is no way to avoid it.

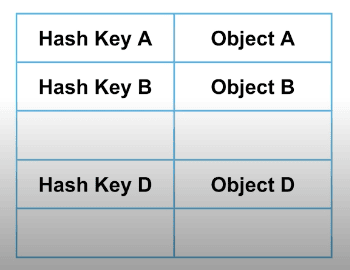

Indeed, just after hash the hash table look up takes place.

As a reminder each node has a hash table. This hash table tracks what’s in cache on that specific node.

Each request that comes through generates its own hash key.

Varnish tries to match that generated hash key with a cache response on the table.

Steps :

1) Request A arrives

2) Hash is generated from URL for request A

3) On the node we try to match this hash with an existing object mapped with this hash.

4) If this hash exists in the table, then it’s a HIT

5) If this hash does not exist in the table, then it’s a MISS

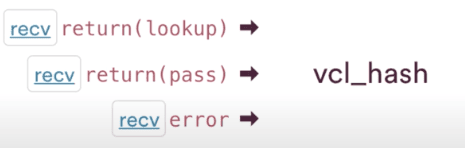

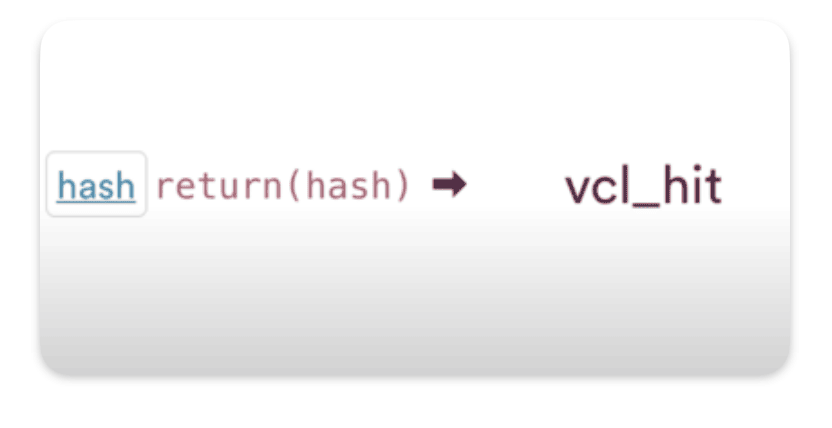

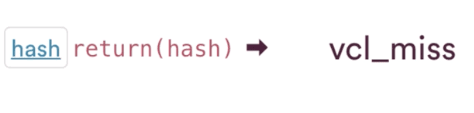

How requests come in VCL_hash ?

Everything comes from receive, no matter what requests pass through hash. Either VCL_rcv asks for a lookup in the hash table or a pass if we want the request to go to the origin.

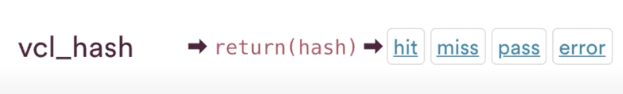

How requests exit in VCL_hash ?

The transition call out is just return hash.

The return lookup, can go to either hit or miss.

The VCL_hash subroutine in details

sub vcl_hash {

#--FASTLY HASH BEGIN

#if unspecified fall back to normal

{

set req.hash += req.url;

set req.hash += req.http.host;

set req.hash += req.vcl.generation;

return (hash);

}

#--FASTLY HASH END

}

The vcl_hash routine is relatively short, and it demonstrates how the hash key is generated.

We have already discussed how it’s generated in the purge article, especially the last part regarding the generation number. This number is used to purge as we bump the generation number by one to make it unreachable…

// www.example.com/filepath1/?abc=123

www. example.com === req.host

"/filepath1/?abc=123" === req.URL

Customize the hash key

It could be useful to customize the hash key, especially if the content varies, but the URL doesn’t.

An example, if the content varies based on the language.

{

set req.hash += req.url;

set req.hash += req.http.host;

set req.hash += req.vcl.generation;

set req.hash += req.vcl.Accept-Language;

return (hash);

}

⚠️ Warning : Adding an extra parameter to the hash will act as a purge-all at first, as all the requested data after this update will get a new hash.

⚠️ Warning : The accept-language header is a relatively safe use case since it doesn’t have much variability in it. If, on the other hand, you use a header like user agent, which lacks standardization and contains a wide range of inputs, your cache hit ratio will suffer significantly due to the large variance within that header.

👌 Good idea : A good idea would be to use the vary header before trying to tweak the hash key. The vary header will keep up to 200 variations or versions of the response object under one hash key.

VCL_hash recap :

• This is where the hash key is generated.

• Changing the Hash Key acts as a Purge All.

• See if Vary Header is better solution before changing the hash key.

• Changing the hash inputs after vcl_hash can cause issues with shielding

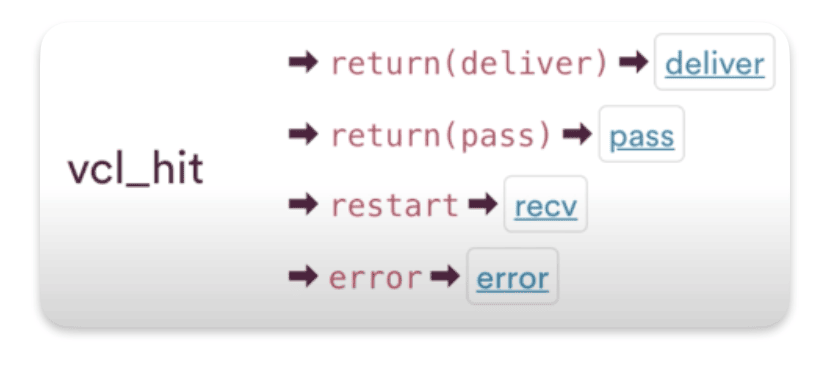

VCL_hit

VCL_hit runs if we find a match in the hashtable for the hashkey, in other words, it means we found the object in the cache.

How requests come in VCL_hit ?

The only way requests go to VCL_hit is from VCL_hash, as I said earlier if we end up in vcl_hit there’s a match.

How requests exit from VCL_hit ?

To exit VCL_hit you can still pass, restart or even error. And the default exit call is return deliver.

The VCL_hit subroutine in details

sub vcl_hit {

#--FASTLY HIT BEGIN

# we cannot reach obj.ttl and obj.grace in deliver, save them when we can in vcl_hit

set req.http.Fastly-Tmp-Obj-TTL = obj.ttl;

set req.http.Fastly-Tmp-Obj-Grace = obj.grace;

{

set req.http.Fastly-Cachetype = "HIT";

}

#--FASTLY HIT END

if (!obj.cacheable) {

return(pass);

}

return(deliver);

}

Code explanation :

# we cannot reach obj.ttl and obj.grace in deliver, save them when we can in vcl_hit

set req.http.Fastly-Tmp-Obj-TTL = obj.ttl;

set req.http.Fastly-Tmp-Obj-Grace = obj.grace;

As the comment says, obj.ttl and obj.grace are not available in delivery, so we have to copy those values in temporary variables. To transfer them from one routine to another, we can use headers.

The fetch process happens on the fetch server using the subroutines hit, pass, miss, and fetch and certain variables, like the object variable, that will not be passed back to deliver.

At the opposite certain variables, like the request headers, will get passed from hit or fetch back to deliver.

{

set req.http.Fastly-Cachetype = "HIT";

}

Here, we simply set an internal header to mark the request as a HIT.

if (!obj.cacheable) {

return(pass);

}

Here if the object in cache is not cachable then we call a return(pass)

The use case here could be that at the end you run a logic that decides to pass, even if we are already in vlc_hit. Then we could set obj.cacheable = false.

return(deliver);

Then of course we finish up with return deliver, that’s our default call, to exit VCL hit.

Takeaways

In vcl_hit it’s always possible to request a fresh version from the origin by your calling return pass. The cached object still remains in cache.

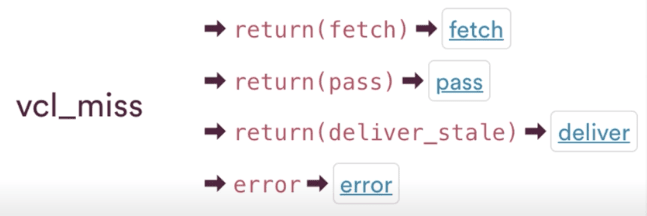

VCL_miss

VCL_miss like VCL_hit and pass and fetch are on the fetch server.

How requests come in VCL_miss ?

VCL_miss is triggered when :

- We don’t have an entry at all for that hash key

- We have a match for the hash key, but the object has expired ( Its TTL has run out )

NB : It’s always possible to call a PASS in MISSif you change your min at last minute.

How requests exit from VCL_miss ?

Our default exit call is a return(fetch), We are going to go and fetch a response from the backend.

We can call return(pass) to go to the pass sub-routine instead.

We can call return(deliver_stale) when the TTL have expiered but we set rules to allow the delivery of a stale object with deliver stale option or stale while revalidate or stale if error

Last transition call is error, which takes us to VCL error

The VCL_miss subroutine in details

sub vcl_miss {

#--FASTLY MISS BEGIN

# this is not a hit after all, clean up these set in vcl_hit

unset req.http.Fastly-Tmp-Obj-TTL;

unset req.http.Fastly-Tmp-Obj-Grace;

{

if (req.http.Fastly-Check-SHA1) {

error 550 "Doesnt exist";

}

#--FASTLY BEREQ BEGIN

{

{

if (req.http.Fastly-FF) {

set bereq.http.Fastly-Client = "1";

}

}

{

# do not send this to the backend

unset bereq.http.Fastly-Original-Cookie;

unset bereq.http.Fastly-Original-URL;

unset bereq.http.Fastly-Vary-String;

unset bereq.http.X-Varnish-Client;

}

if (req.http.Fastly-Temp-XFF) {

if (req.http.Fastly-Temp-XFF == "") {

unset bereq.http.X-Forwarded-For;

} else {

set bereq.http.X-Forwarded-For = req.http.Fastly-Temp-XFF;

}

# unset bereq.http.Fastly-Temp-XFF;

}

}

#--FASTLY BEREQ END

#;

set req.http.Fastly-Cachetype = "MISS";

}

#--FASTLY MISS END

return(fetch);

}

Code explanation :

unset req.http.Fastly-Tmp-Obj-TTL;

unset req.http.Fastly-Tmp-Obj-Grace;

If our request went to hit but restarted and ended up in MISS we clean those headers HIT set.

if (req.http.Fastly-Check-SHA1) {

error 550 "Doesnt exist";

}

A condition for Fastly check SHa1, giving an error 550 code. This is for internal testing only for Fastly.

{

{

if (req.http.Fastly-FF) {

set bereq.http.Fastly-Client = "1";

}

}

Checking to see if the Fastly forwarded for header is present. If it is, then we set a back-end request header for the Fastly client. This allows customers and developers to use a header to check if this request is coming from Fastly.

# do not send this to the backend

unset bereq.http.Fastly-Original-Cookie;

unset bereq.http.Fastly-Original-URL;

unset bereq.http.Fastly-Vary-String;

unset bereq.http.X-Varnish-Client;

Those headers are specific to Fastly, and the idea here is to remove them before he reaches the backend.

if (req.http.Fastly-Temp-XFF) {

if (req.http.Fastly-Temp-XFF == "") {

unset bereq.http.X-Forwarded-For;

} else {

set bereq.http.X-Forwarded-For = req.http.Fastly-Temp-XFF;

}

# unset bereq.http.Fastly-Temp-XFF;

}

Modifications to the Fastly temp X forwarded for header

#--FASTLY BEREQ END

#;

set req.http.Fastly-Cachetype = "MISS";

}

#--FASTLY MISS END

return(fetch);

}

We are setting again the Fastly cache type as miss for internal use.

Then we have the transition call to default transition call of return fetch that will actually trigger the backend request

Takeways

Last Stop before the request goes to the backend

• Last minute changes to request.

• Last chance to PASS on the request.

• This is where WAF lives, before the request to the backend ( where we plug it )

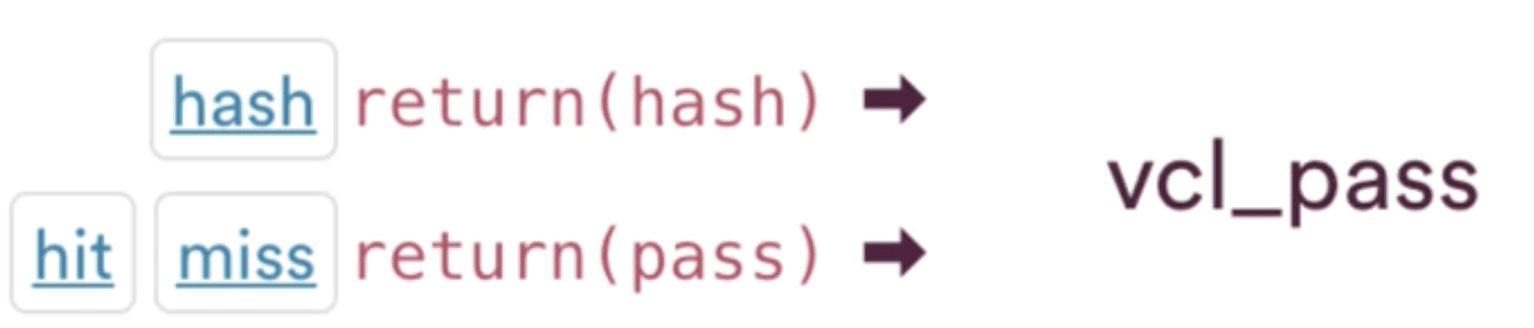

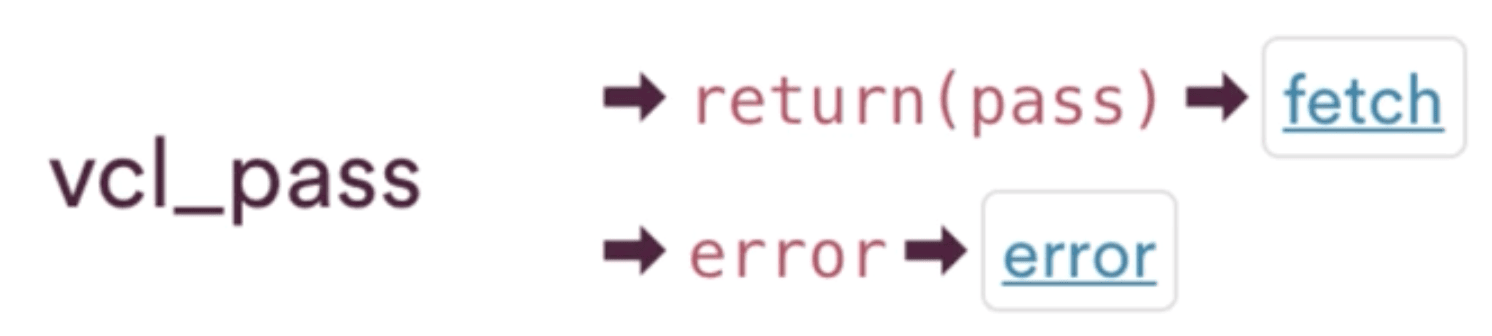

VCL_pass

Pass is the sub routine we use for the requests we know we don’t want to cache the response.

How requests come in VCL_pass ?

You can get to VCL_pass through, receive, ie, calling return pass there, something we already discussed in this article

You can also endup in PASS through miss or hit as discussed in the above sections.

Hit for pass :

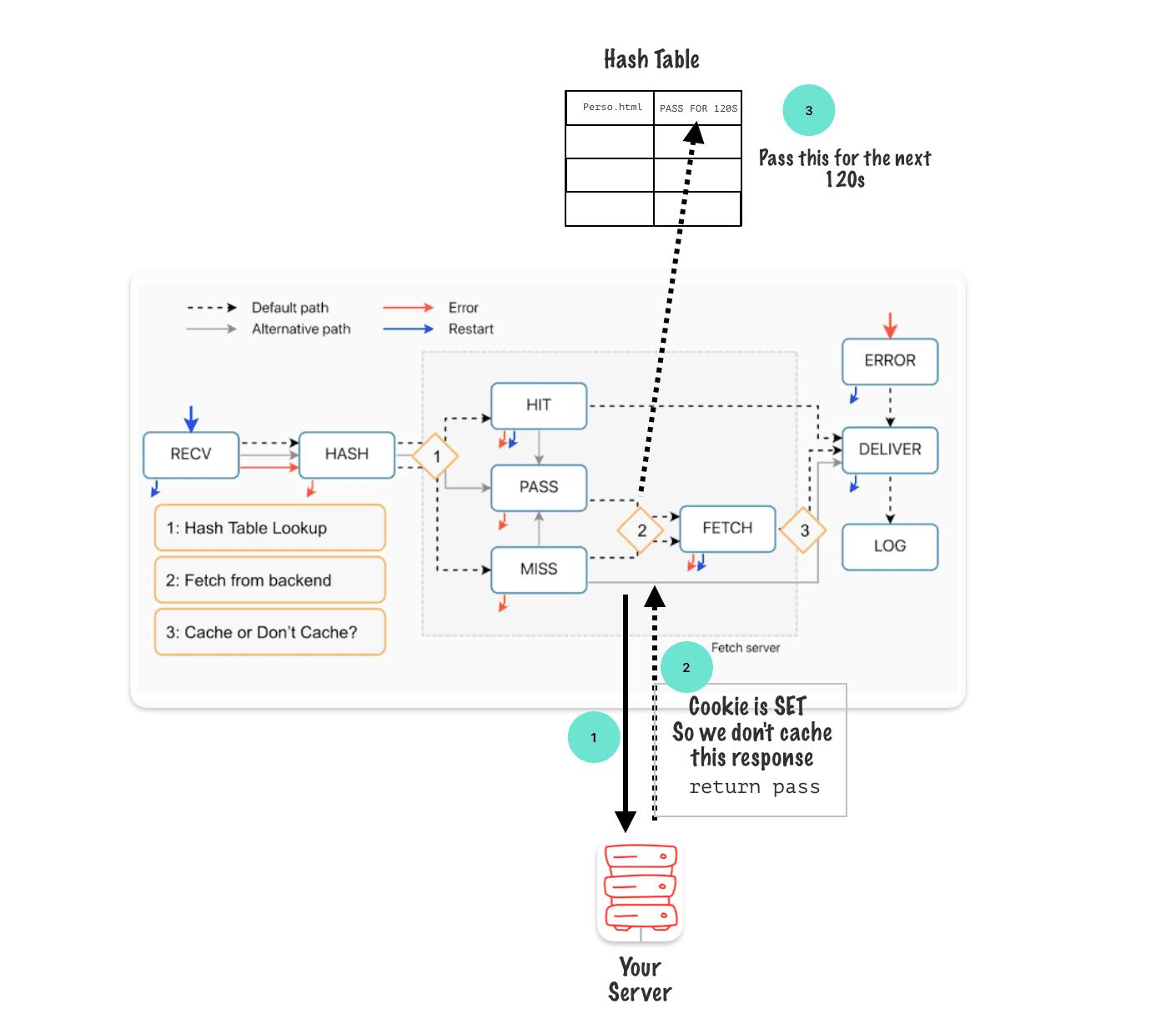

The hit for pass behavior, we execute a return pass in VCL_fetch and the hash table for that node gets an entry for that hash key that says, “Pass for the next default of 120 seconds.” As explained here

How requests exit from VCL_pass ?

Our exit call, our exit transition is return pass.ou can also error out of pass as well.

VCL_pass in detail

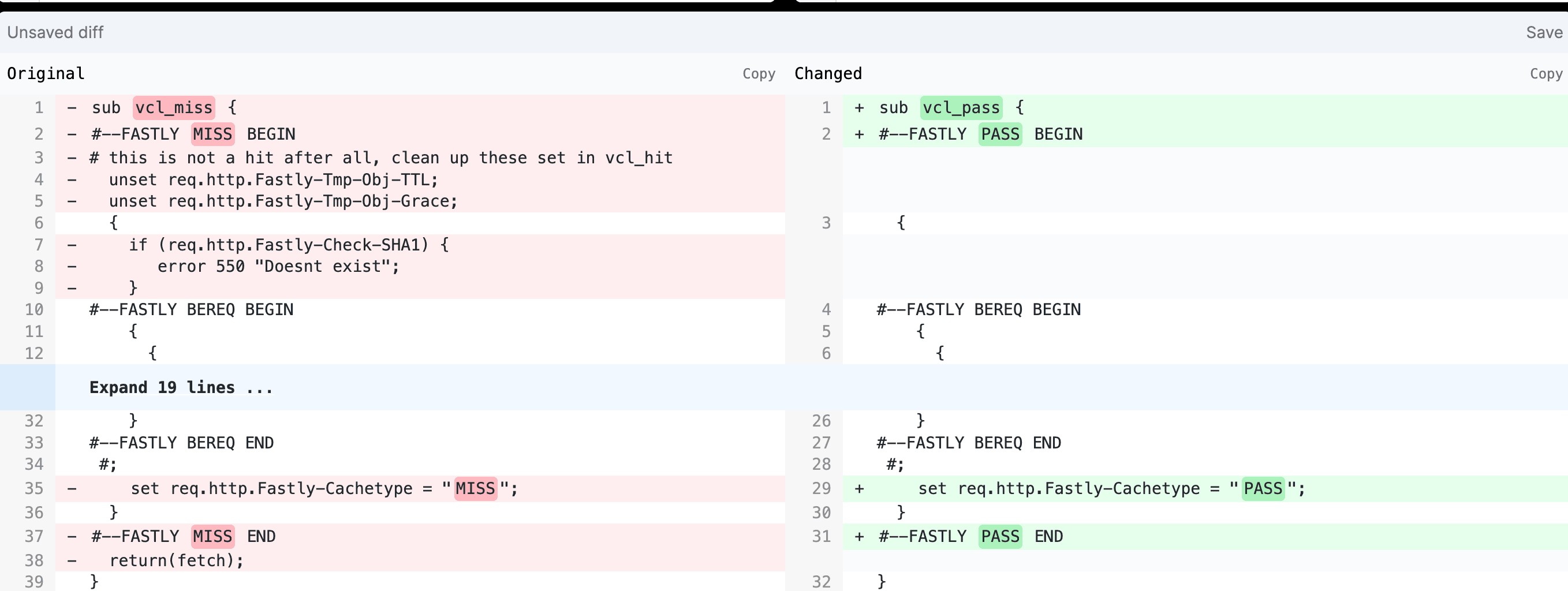

THe code is verry similar to VCL_miss ooking at them in a diff checker with VCL miss on the left and VCL pass on the right, we can see that there’s just a couple of things that have been removed for pass.

Unsetting of those temporary TTLs and temporary grace request headers, they’re not being unset in pass. Those may be passed to the origin. Also, we don’t have the Fastly check SHA1 in place. That’s also been removed. The other thing to point out that’s missing is looking at the end of VCL pass, there’s no default return pass present. Even though it was listed on our diagram there, it’s not actually present and it doesn’t need to be. For the case of VCL pass, the default transition call is there in the background. Since there’s literally only one way to transition out of this subroutine except from error, really the only call is going to be return pass

Takeways for VCL_pass

Last Stop before the request goes to the backend

• Last minute changes to request.

• Best Practice: Any change in MISS, should be made in PASS

and vise versa.

• This is where also WAF lives, before the request to the backend.

Takeways Hash, Hit, Miss and Pass Subroutines

• Vcl_hash is for generating the Hash Key. Proceed with caution.

• Changing hash key inputs after vc|_hash combined w/ shielding affects purge.

• You can still PASS from vcl_hit & vcl_miss.

• Last min changes should happen in both vcl_miss & vcl_pass

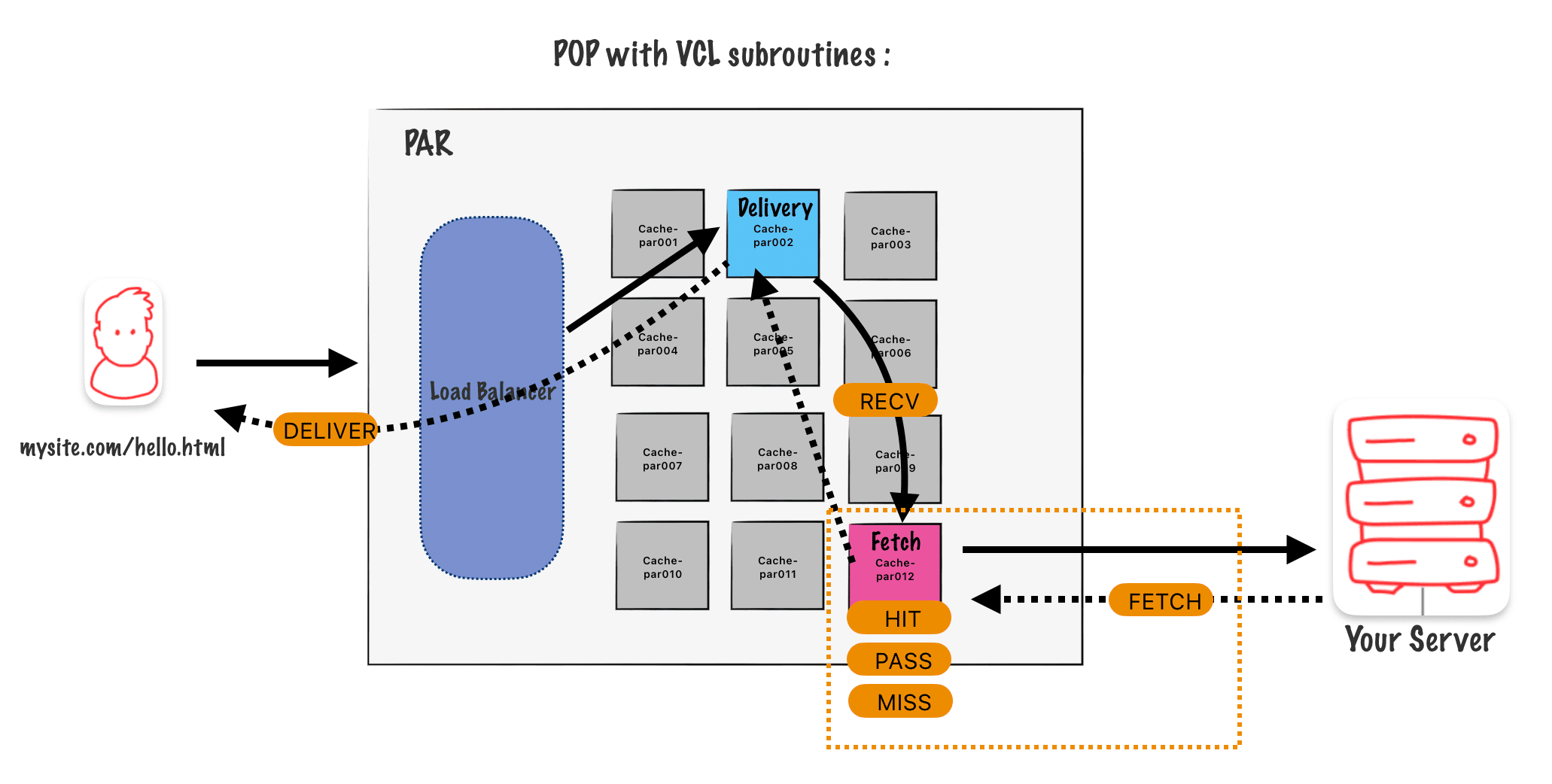

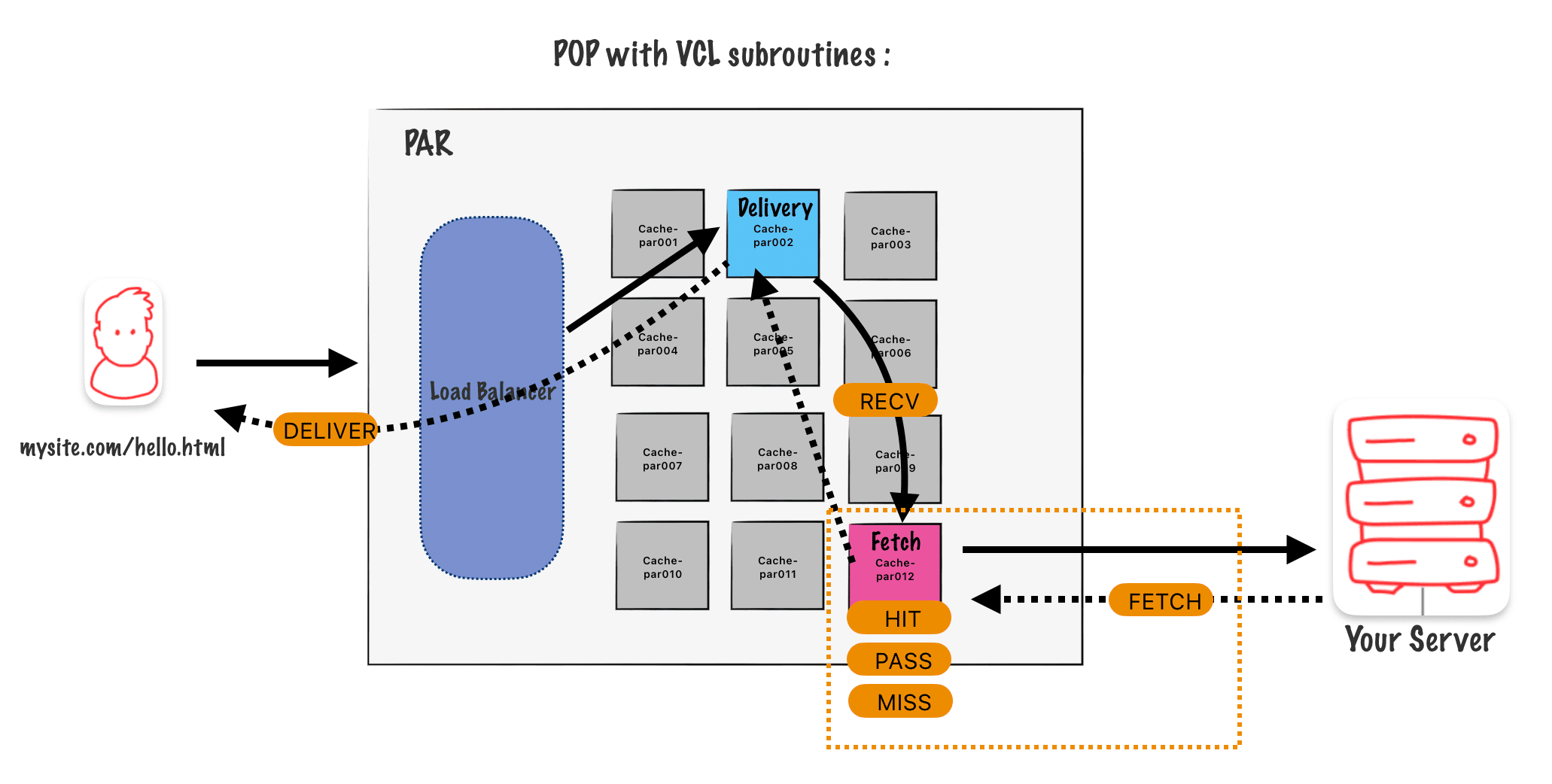

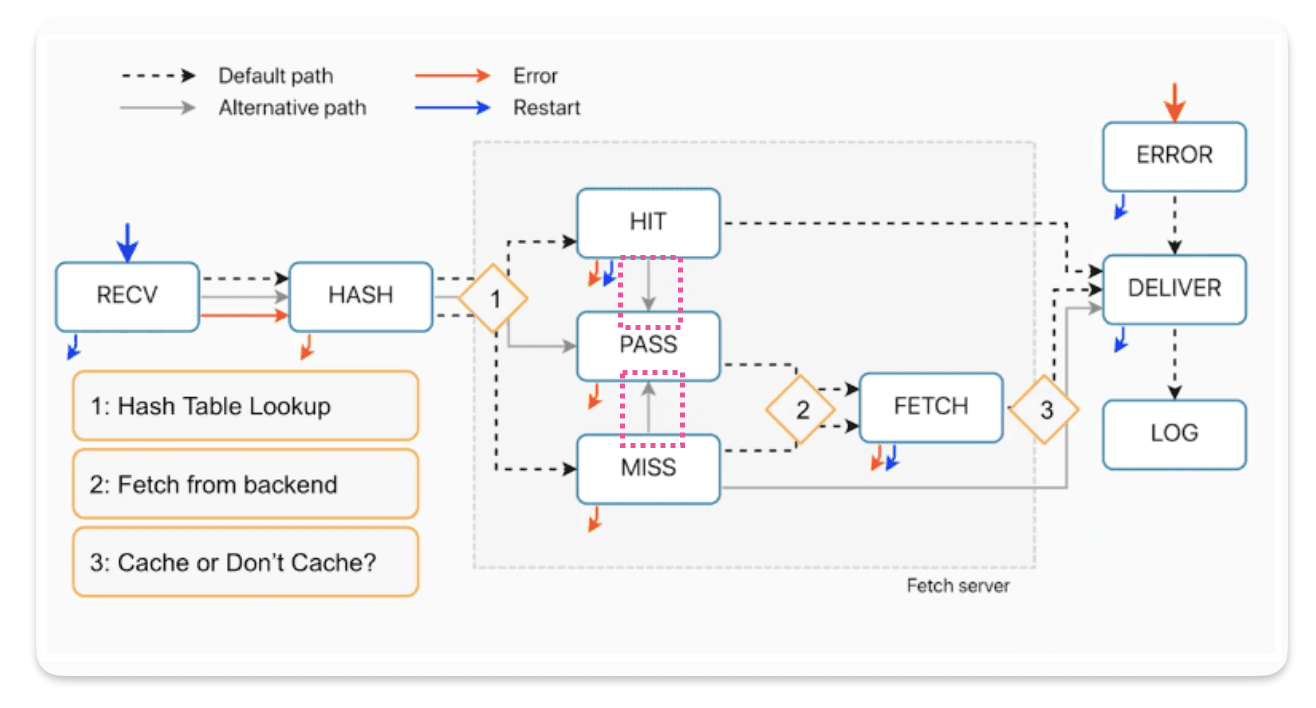

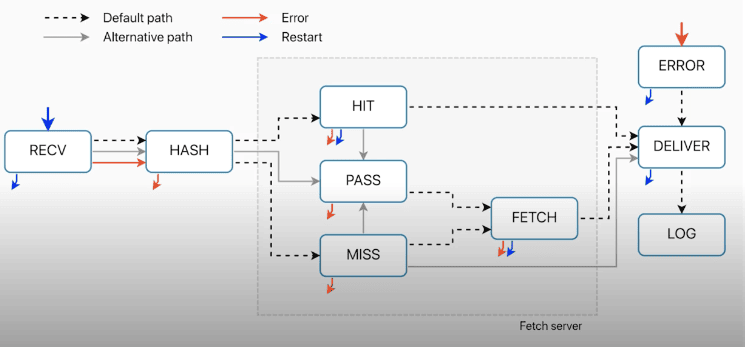

Varnish state machine flow

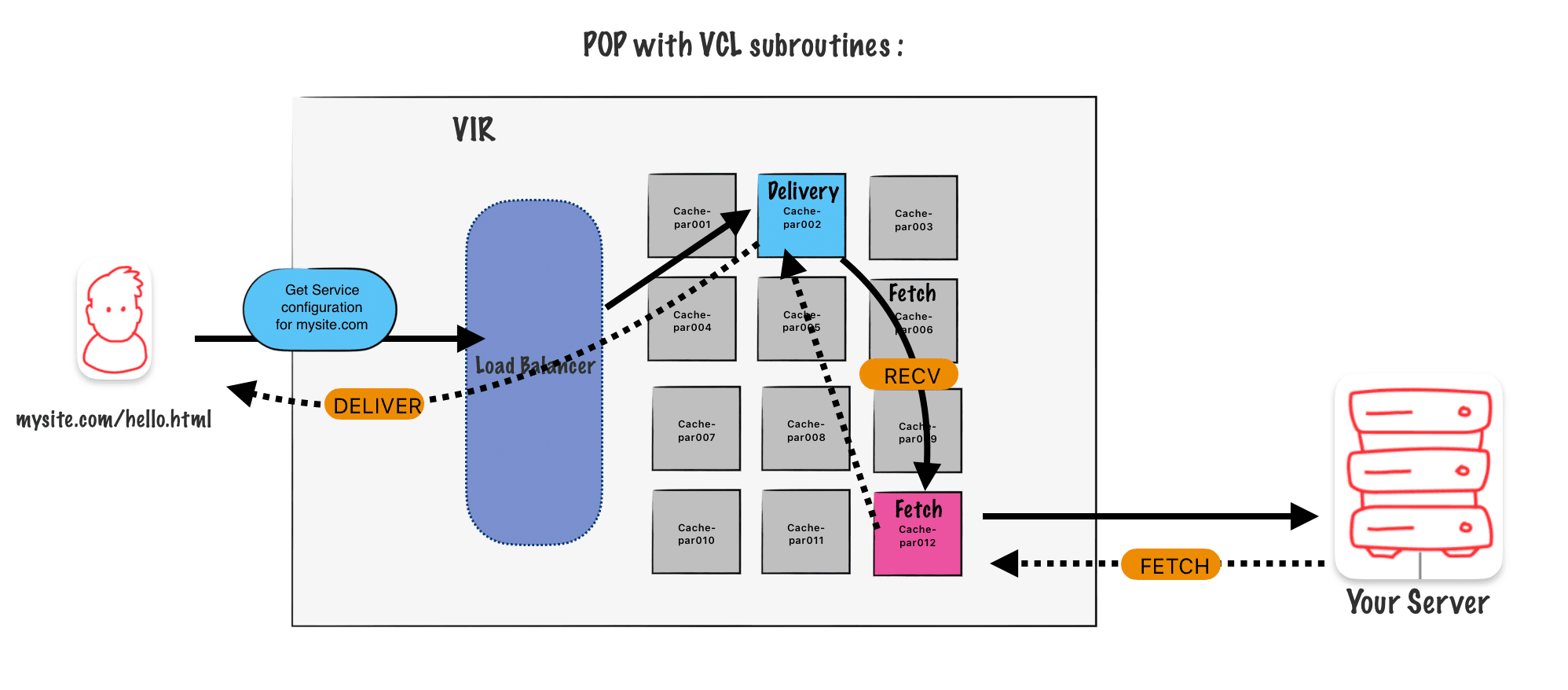

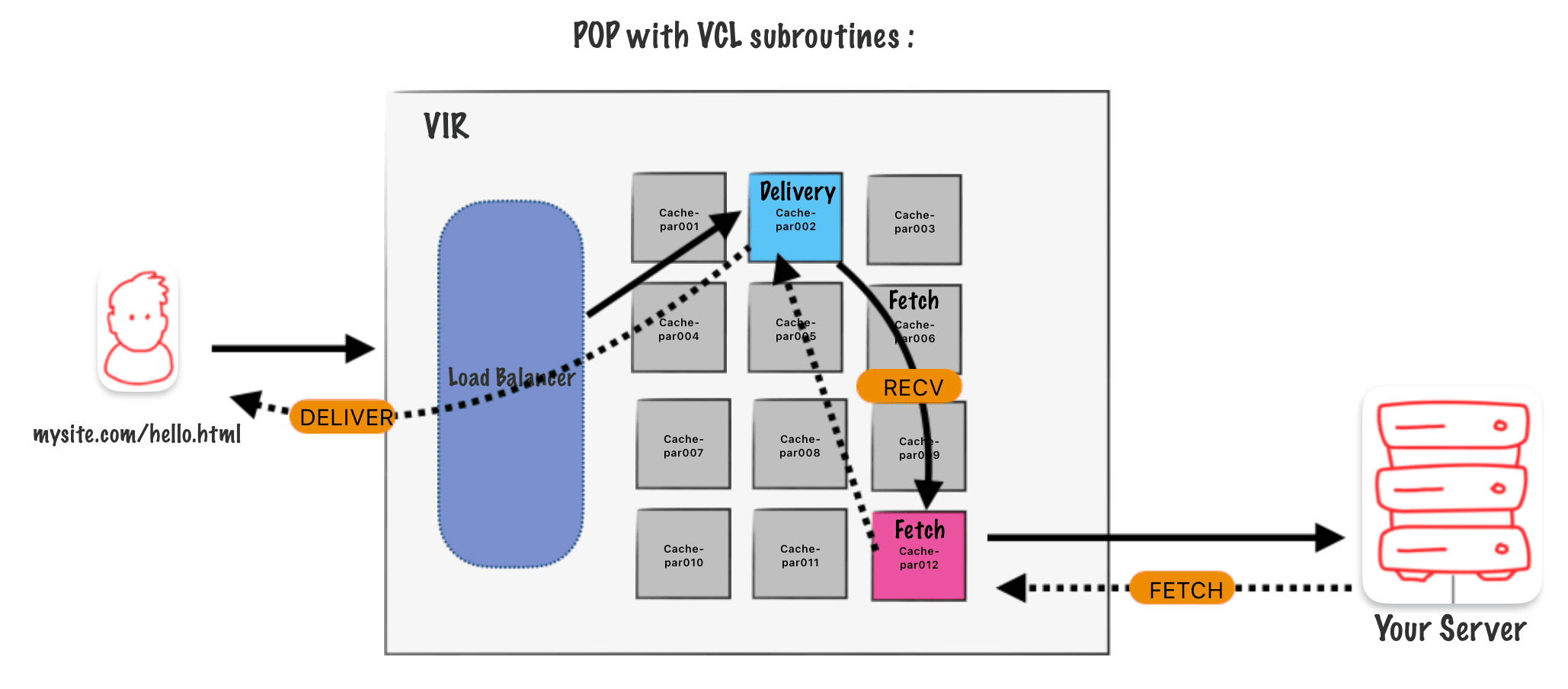

When a request comes into Fastly, it’s assigned out from a load balancer to one of the nodes on the POP, and that will act as the delivery node.

Then there is a domain lookup where the request host header, the value there, say example.com is looked up on a giant table on the node to see which service configuration has that matching domain. The attached service configuration is then run and this is what we’re looking at here is all the subroutines that make up that service configuration.

We assume that there’s caching that’s attempting to go on with this request. So starting on our left, when a request comes in, receive is the first subroutine to run. We can follow that dash line as it goes from receive to hash.

After hash is the hash table lookup on the node to see if the item is already cached.

And then it’ll split either between hit or miss

This becomes a decision point:

- If we have the item already, it’s a hit and we run the hit subroutine.

Following through from hit, we can follow that same dotted line. We have the item in cache. It’s handed over to the deliver subroutine, and deliver runs. And then it’s handed off to the end user as a response. Going back to our hash table after the hash subroutine, if we don’t have the item already on the table, we don’t have a match. It’s not in cache, it’s a miss. -

If do not have the item already, it’s a miss. Then the miss subroutine will run. The second action or process, and this is the fetch from backend. So if we don’t have the item, we of course need to request it from the backend. This is where we fetch the object. After this process, we then run the fetch subroutine.

After we run fetch we have an other process and this is where we actually cache or don’t cache the response object. Either way, whatever comes out of fetch, whether we cache it or not is handed off to then deliver, the deliver subroutine runs, and then we send off the actual response to the end user.

VCL_recv

This is our first subroutine, it’s the first point of contact and it’s used for :

- normalizing clients’ input

- normalize headers

- normalize the request URL

- Strip some query parameters

- Switching between the backends (allocating a specific backend to a request)

- Apply authentication ( check JWT, API Keys, geolocation, Ips, Paywallls…)

- Triggering synthetic responses for known paths

- PASS on request that should not be cahed

VCL_recv is the best place to make those changes to standardize client’s inputs It’s very similar to a an Node.js express Middleware.

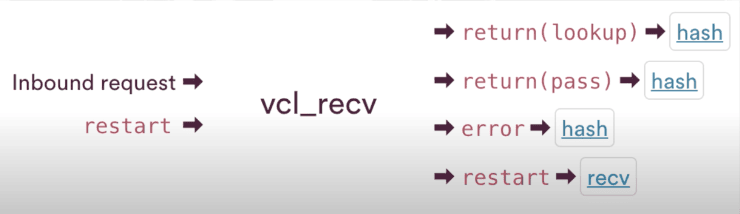

How request come and exit from VCL_recv subroutine ?

How they enter in VCL_recv ?

- inbound request : The first way requests enter in VCL_recv

- restart : If restart is called, you leave whatever subroutine you’re in and it returns you to the beginning of the VCL flow

How they exit in VCL_recv ?

- return lookup : The default way to exit, Return lookup is referencing a lookup call on the hash table. You’re looking to see if something is in cache

- return pass : If you don’t want to cache

- error : Calling error takes you to the error subroutine

- restart : If restart is called, you leave whatever subroutine you’re in and it returns you to the beginning of the VCL flow

Where requests go after VCL_recv ?

After receive all requests go to hash, but after they go to hash, they are all going to end up at different places.

Default path : Hash then cache table lookup then eihter a cache HIT or cache MISS

Calling Pass in receive : Hash which generates hash key goes to that hash table, but then goes to pass.

Error : Hash ad then straight to error ( as we don’t want to cache errors )

The VCL_recv subroutine in details

sub vcl_recv {

#--FASTLY RECV BEGIN

if (req.restarts == 0) {

if (!req.http.X-Timer) {

set req.http.X-Timer = "S" time.start.sec "." time.start.usec_frac;

}

set req.http.X-Timer = req.http.X-Timer ",VS0";

}

declare local var.fastly_req_do_shield BOOL;

set var.fastly_req_do_shield = (req.restarts == 0);

# default conditions

# end default conditions

#--FASTLY RECV END

if (req.request != "HEAD" && req.request != "GET" && req.request != "FASTLYPURGE") {

return(pass);

}

return(lookup);

}

Let’s analyze this code :

if (req.restarts == 0) {

if (!req.http.X-Timer) {

set req.http.X-Timer = "S" time.start.sec "." time.start.usec_frac;

}

set req.http.X-Timer = req.http.X-Timer ",VS0";

}

Here is the inclusion of a timer header req.http.X-Timer

This is used for our timing metrics. We add it at the very beginning once we get it in receive, and it gets tied up later on in deliver at the end. This is only initialized, if the number of restarts is zero.

declare local var.fastly_req_do_shield BOOL;

set var.fastly_req_do_shield = (req.restarts == 0);

Then we have some shield variables that are being declared and set.

if (req.request != "HEAD" && req.request != "GET" && req.request != "FASTLYPURGE") {

return(pass);

}

If the request method is not a head, and the request method is not a get, and the request is not a Fastly purge call, then it’ll return pass. So if it’s not any of these three things, we are not going to cache it, we call the pass behavior.

return(lookup);

Then at the end of the receive subroutine, we have our default transition call, which is returned lookup.

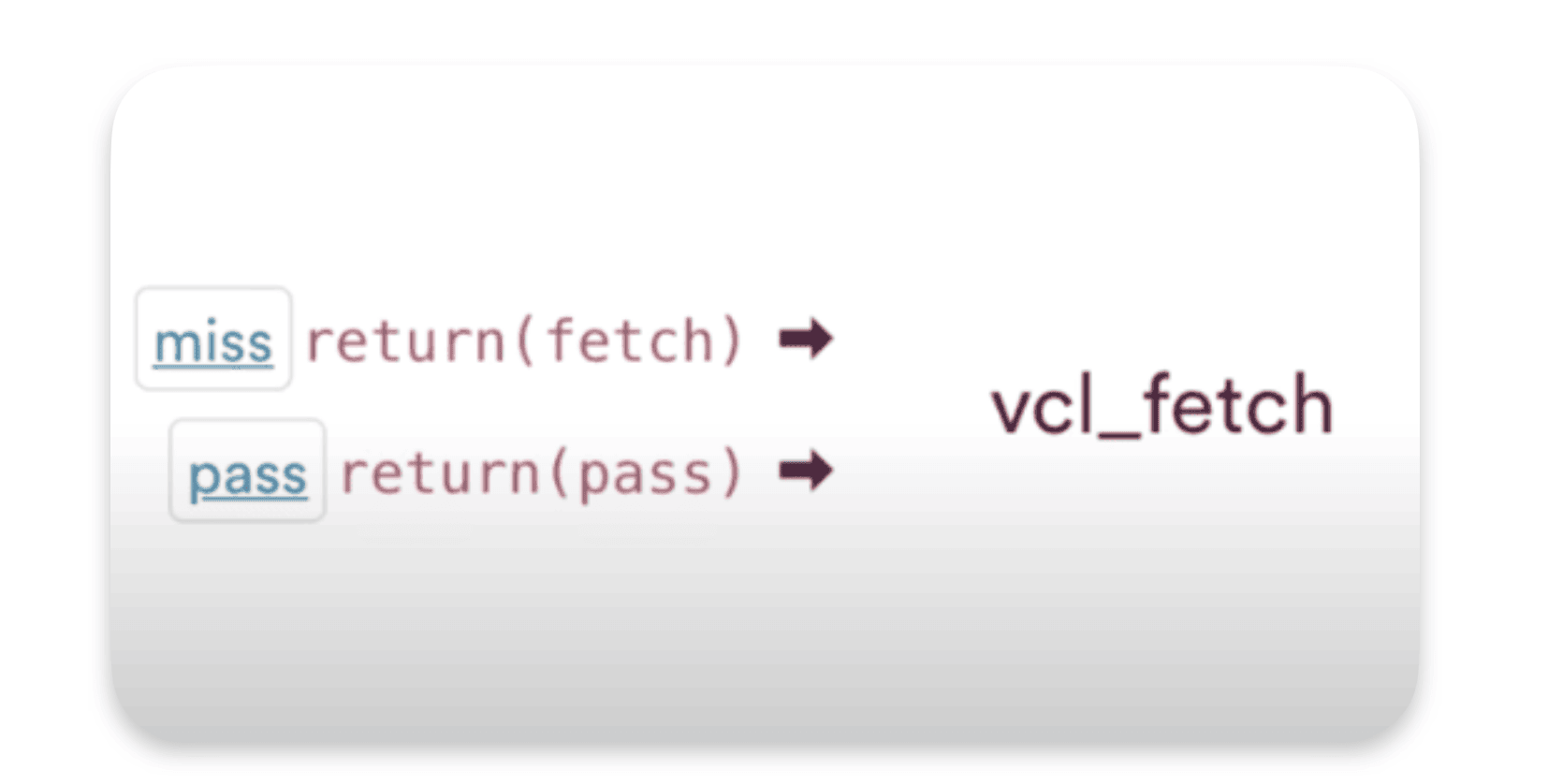

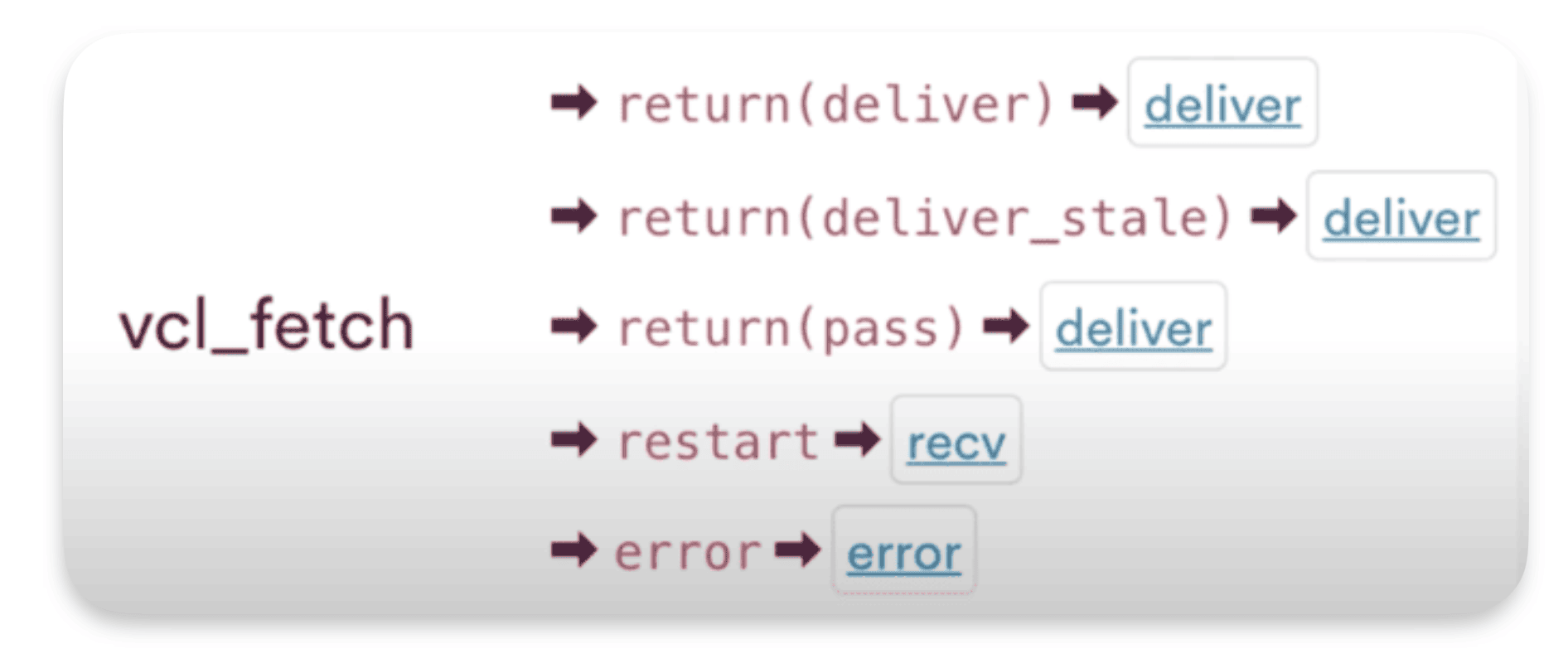

VCL_fetch

How requests enter in VCL_fetch ?

We go to fetch after a PASS or a MISS, if it’s a PASS then we should get the data from our backend. Same thing for MISS, as we don’t have it in the cache we have to grab the data from our backend and then put it in the cache.

VCL_fetch it’s used for :

- Set a default TTL

- Set specific TTLs for content based on things like file path, content type or other relevant variables.

- Modify or remove response headers set from the origin or adding entirely new ones.

- configure rules for serving stale content, using

beresp.stale-while-revalidateand orberesp.stale-if-error

When we get that backend response before fetch runs, Varnish looks for the presence of any cache control headers that Fastly considers valid. If we find them and we find values that we can use, we will use them to set the TTL for this particular response object.

How requests exit in VCL_fetch ?

To exit VCL fetch, the default transition is return deliver.

- return deliver

- return deliver stale : Deliver stale is related to those serving stale content options

- return pass : Will not cache, and it will still head off to deliver.

- restart : goes back to receive

- error : which will bypass receive and go straight to error.

By the way we are expecting to cache the responses that we get from the backend, and this would be the default transition to do so.

The VCL_fetch routine in details

sub vcl_fetch {

declare local var.fastly_disable_restart_on_error BOOL;

#--FASTLY FETCH BEGIN

# record which cache ran vcl_fetch for this object and when

set beresp.http.Fastly-Debug-Path = "(F " server.identity " " now.sec ") " if(beresp.http.Fastly-Debug-Path, beresp.http.Fastly-Debug-Path, "");

# generic mechanism to vary on something

if (req.http.Fastly-Vary-String) {

if (beresp.http.Vary) {

set beresp.http.Vary = "Fastly-Vary-String, " beresp.http.Vary;

} else {

set beresp.http.Vary = "Fastly-Vary-String, ";

}

}

#--FASTLY FETCH END

if (!var.fastly_disable_restart_on_error) {

if ((beresp.status == 500 || beresp.status == 503) && req.restarts < 1 && (req.request == "GET" || req.request == "HEAD")) {

restart;

}

}

if(req.restarts > 0 ) {

set beresp.http.Fastly-Restarts = req.restarts;

}

if (beresp.http.Set-Cookie) {

set req.http.Fastly-Cachetype = "SETCOOKIE";

return (pass);

}

if (beresp.http.Cache-Control ~ "private") {

set req.http.Fastly-Cachetype = "PRIVATE";

return (pass);

}

if (beresp.status == 500 || beresp.status == 503) {

set req.http.Fastly-Cachetype = "ERROR";

set beresp.ttl = 1s;

set beresp.grace = 5s;

return (deliver);

}

if (beresp.http.Expires || beresp.http.Surrogate-Control ~ "max-age" || beresp.http.Cache-Control ~"(?:s-maxage|max-age)") {

# keep the ttl here

} else {

# apply the default ttl

set beresp.ttl = 3600s;

}

return(deliver);

}

Let’s explore the basic code in VCL_fetch

set beresp.http.Fastly-Debug-Path = "(F " server.identity " " now.sec ") " if(beresp.http.Fastly-Debug-Path, beresp.http.Fastly-Debug-Path, "");

Fastly debug headers can collect and expose that information when you send those headers as a request header. It’ll add in some additional response debugging headers.

To get this header in your response call one of you url with this header : 'Fastly-Debug': '1'

if (req.http.Fastly-Vary-String) {

if (beresp.http.Vary) {

set beresp.http.Vary = "Fastly-Vary-String, " beresp.http.Vary;

} else {

set beresp.http.Vary = "Fastly-Vary-String, ";

}

}

A generic mechanism to check if your backend uses the Vary header which is used when the reponse vary based on something ( User-agent for example )

if (!var.fastly_disable_restart_on_error) {

if ((beresp.status == 500 || beresp.status == 503) && req.restarts < 1 && (req.request == "GET" || req.request == "HEAD")) {

restart;

}

}

If you get a 500 or a 503 and the number of restarts is less than one and the request type is a get or a head, then it will cause a restart to happen.

This mechanism will be triggered only once (req.restarts < 1)

if(req.restarts > 0 ) {

set beresp.http.Fastly-Restarts = req.restarts;

}

If the number of restarts is greater than zero. So we’ve already restarted. Then we’re going to set a backend response header for Fastly restarts equal to the number of restarts

if (beresp.http.Set-Cookie) {

set req.http.Fastly-Cachetype = "SETCOOKIE";

return (pass);

}

If there is a set cookie header set by the backend. Then this response is unique to the user and we don’t cache it.

if (beresp.http.Cache-Control ~ "private") {

set req.http.Fastly-Cachetype = "PRIVATE";

return (pass);

}

If control header has a value of private then we pass.

if (beresp.status == 500 || beresp.status == 503) {

set req.http.Fastly-Cachetype = "ERROR";

set beresp.ttl = 1s;

set beresp.grace = 5s;

return (deliver);

}

If the response from the backend is an error a 500 or a 503 then we’re cashing them for just a second set beresp.ttl = 1s;

This one second gap where we temporarily serve this from cache can help offload the strain to that origin and help it to recover and that’s why we just do a return deliver because we are caching that response, but only for one second.

if (beresp.http.Expires || beresp.http.Surrogate-Control ~ "max-age" || beresp.http.Cache-Control ~"(?:s-maxage|max-age)") {

# keep the ttl here

} else {

# apply the default ttl

set beresp.ttl = 3600s;

}

So if there’s an expires header, if there’s a surrogate control value with max age or a cache control value with either surrogate max age or max age, that implies that we would be able to pull a TTL out of those values and we would keep the TTL

return(deliver);

Then if none of these other conditions trigger a return pass or return deliver, we always have our default return deliver without any condition at the end of the subroutine.

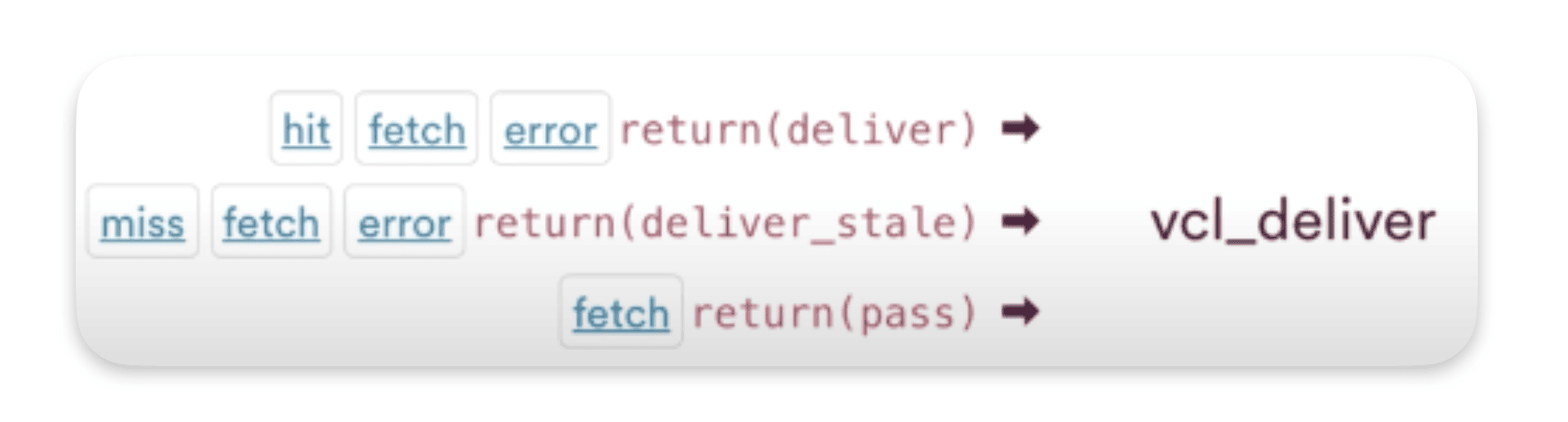

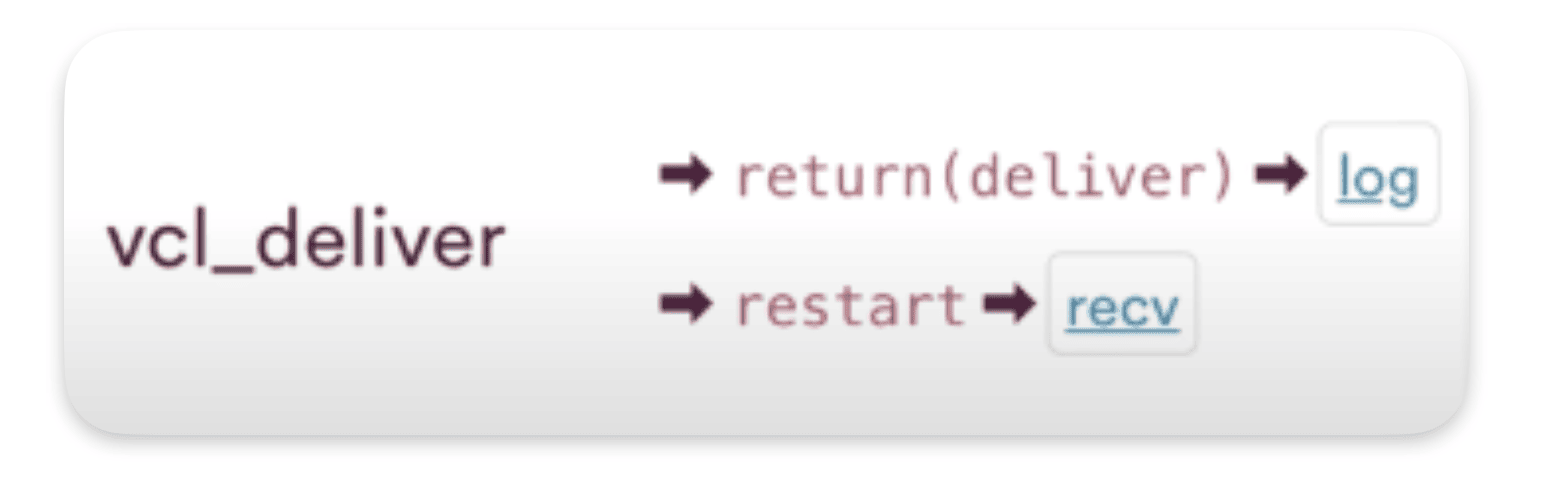

VCL_deliver

Deliver is the last set routine before the log subroutine runs. Deliver runs before the first byte of the response is sent to the user. It’s also the last chance to modify your response, headers…

Deliver runs on every single response no matter if the response comes from the cache etc…

It’s an ideal place for adding debugging information or user specific session data that cannot be shared with other users ( adding debug headers…)

How requests enter in VCL_deliver ?

- hit fetch error

- miss fetch *error**

- fetch :

return(pass):from the fetch subroutine you can also call return pass to not cache and pass off the response to VCL deliver.

How requests exit in VCL_deliver ?

- return deliver : the transition to exit VCL deliver is return deliver. That is the default, it is referencing itself.

- restart : restart go back to the beginning at receive.

Let’s explore the VCL for deliver :

sub vcl_deliver {

#--FASTLY DELIVER BEGIN

# record the journey of the object, expose it only if req.http.Fastly-Debug.

if (req.http.Fastly-Debug || req.http.Fastly-FF) {

set resp.http.Fastly-Debug-Path = "(D " server.identity " " now.sec ") "

if(resp.http.Fastly-Debug-Path, resp.http.Fastly-Debug-Path, "");

set resp.http.Fastly-Debug-TTL = if(obj.hits > 0, "(H ", "(M ")

server.identity

if(req.http.Fastly-Tmp-Obj-TTL && req.http.Fastly-Tmp-Obj-Grace, " " req.http.Fastly-Tmp-Obj-TTL " " req.http.Fastly-Tmp-Obj-Grace " ", " - - ")

if(resp.http.Age, resp.http.Age, "-")

") "

if(resp.http.Fastly-Debug-TTL, resp.http.Fastly-Debug-TTL, "");

set resp.http.Fastly-Debug-Digest = digest.hash_sha256(req.digest);

} else {

unset resp.http.Fastly-Debug-Path;

unset resp.http.Fastly-Debug-TTL;

unset resp.http.Fastly-Debug-Digest;

}

# add or append X-Served-By/X-Cache(-Hits)

{

if(!resp.http.X-Served-By) {

set resp.http.X-Served-By = server.identity;

} else {

set resp.http.X-Served-By = resp.http.X-Served-By ", " server.identity;

}

set resp.http.X-Cache = if(resp.http.X-Cache, resp.http.X-Cache ", ","") if(fastly_info.state ~ "HIT(?:-|\z)", "HIT", "MISS");

if(!resp.http.X-Cache-Hits) {

set resp.http.X-Cache-Hits = obj.hits;

} else {

set resp.http.X-Cache-Hits = resp.http.X-Cache-Hits ", " obj.hits;

}

}

if (req.http.X-Timer) {

set resp.http.X-Timer = req.http.X-Timer ",VE" time.elapsed.msec;

}

# VARY FIXUP

{

# remove before sending to client

set resp.http.Vary = regsub(resp.http.Vary, "Fastly-Vary-String, ", "");

if (resp.http.Vary ~ "^\s*$") {

unset resp.http.Vary;

}

}

unset resp.http.X-Varnish;

# Pop the surrogate headers into the request object so we can reference them later

set req.http.Surrogate-Key = resp.http.Surrogate-Key;

set req.http.Surrogate-Control = resp.http.Surrogate-Control;

# If we are not forwarding or debugging unset the surrogate headers so they are not present in the response

if (!req.http.Fastly-FF && !req.http.Fastly-Debug) {

unset resp.http.Surrogate-Key;

unset resp.http.Surrogate-Control;

}

if(resp.status == 550) {

return(deliver);

}

#default response conditions

#--FASTLY DELIVER END

return(deliver);

}

Let’s explore the deliver sub routine in details

if (req.http.Fastly-Debug || req.http.Fastly-FF) {

set resp.http.Fastly-Debug-Path = "(D " server.identity " " now.sec ") "

if(resp.http.Fastly-Debug-Path, resp.http.Fastly-Debug-Path, "");

set resp.http.Fastly-Debug-TTL = if(obj.hits > 0, "(H ", "(M ")

server.identity

if(req.http.Fastly-Tmp-Obj-TTL && req.http.Fastly-Tmp-Obj-Grace, " " req.http.Fastly-Tmp-Obj-TTL " " req.http.Fastly-Tmp-Obj-Grace " ", " - - ")

if(resp.http.Age, resp.http.Age, "-")

") "

if(resp.http.Fastly-Debug-TTL, resp.http.Fastly-Debug-TTL, "");

set resp.http.Fastly-Debug-Digest = digest.hash_sha256(req.digest);

} else {

unset resp.http.Fastly-Debug-Path;

unset resp.http.Fastly-Debug-TTL;

unset resp.http.Fastly-Debug-Digest;

}

Here we set 3 Fastly debug headers :

resp.http.Fastly-Debug-Path : show which nodes the request used ( the delivery and fetch node)

resp.http.Fastly-Debug-TTL : Includes the TTL information

resp.Fastly-Debug-FF : If shielding is on

# add or append X-Served-By/X-Cache(-Hits)

{

if(!resp.http.X-Served-By) {

set resp.http.X-Served-By = server.identity;

} else {

set resp.http.X-Served-By = resp.http.X-Served-By ", " server.identity;

}

set resp.http.X-Cache = if(resp.http.X-Cache, resp.http.X-Cache ", ","") if(fastly_info.state ~ "HIT(?:-|\z)", "HIT", "MISS");

if(!resp.http.X-Cache-Hits) {

set resp.http.X-Cache-Hits = obj.hits;

} else {

set resp.http.X-Cache-Hits = resp.http.X-Cache-Hits ", " obj.hits;

}

}

« `X-Served-By« « just tells you which node the request passed through. The X cache is going to tell you whether or not it was a hit or a miss. When we looked in cache, did we already have it? Was it hit? If not, was it a miss?

NB : For the X cache response header are hit or miss even when a PASS behavior is called it gets reported out as a miss here on this X cache header

Keep in mind : Miss might be hiding a pass !

http.X-Cache-Hits: The delivery node will say how many times it’s had a hit for this particular object coming out of cache. Keep in mind the delivery nodes gets load balanced across the POP so the X cache hits cna be different.

if (req.http.X-Timer) {

set resp.http.X-Timer = req.http.X-Timer ",VE" time.elapsed.msec;

}

Pulls in the initial X timer value (from VCL_receive) and adds in the time elapsed in milliseconds

# VARY FIXUP

{

# remove before sending to client

set resp.http.Vary = regsub(resp.http.Vary, "Fastly-Vary-String, ", "");

if (resp.http.Vary ~ "^\s*$") {

unset resp.http.Vary;

}

}

if (resp.http.Vary ~ "^\s*$") : if the vary header contains nothing

unset resp.http.X-Varnish;

This is an internal diagnostic header, so it’s just being unset

# Pop the surrogate headers into the request object so we can reference them later

set req.http.Surrogate-Key = resp.http.Surrogate-Key;

set req.http.Surrogate-Control = resp.http.Surrogate-Control;

# If we are not forwarding or debugging unset the surrogate headers so they are not present in the response

if (!req.http.Fastly-FF && !req.http.Fastly-Debug) {

unset resp.http.Surrogate-Key;

unset resp.http.Surrogate-Control;

}

Here we put Surrogate-Key and Surrogate-Control from the response ( resp) to the request.

So it can be used by an other POP if this one is not the last one ( if there’s a shield after that one ).

What the doc says about http.Faslty-FF : this header as a simple mechanism to determine whether the current data center is acting as an edge or a shield

VCL deliver conclusion :

To sum it up, VCL deliver completes entirely before sending the response to the user. It occurs for each response separately. This is where you can include debugging details and session data specific to the user that shouldn’t be shared with others. It’s also your final opportunity to restart. The key transition calls here are return, deliver, and restart.

Takeaways

- Receive:

- Normalize input.

- Select a backend.

- Block at the edge.

- Redirect at the edge.

- Choose not to cache.

- Fetch:

- Set custom TTL.

- Modify headers from the backend.

- Configure rules for serving stale.

- Set default TTL.

- Deliver:

- Runs on every response.

- Adds debugging information.

- Handles user-specific session data.

- Last opportunity to restart.

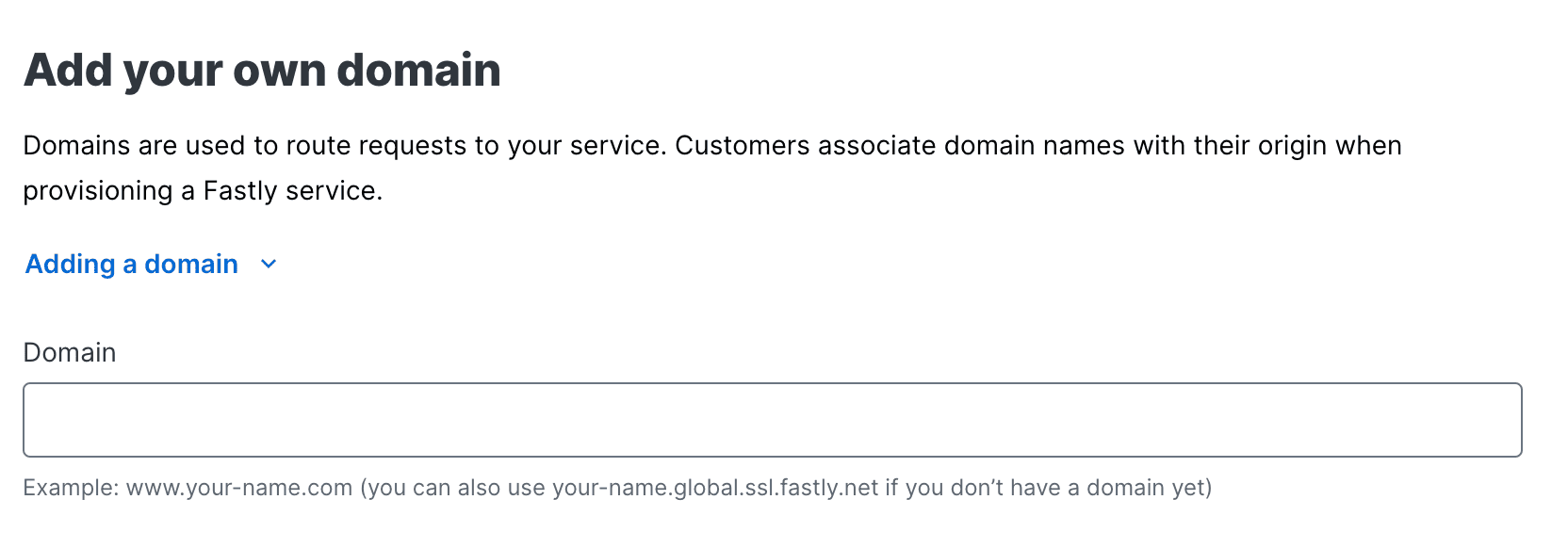

Get started with custom setting and VCL with Fastly

When a request goes to Faslty it goes to the POP and then gets send to one of the node. The node has a master list of all the domains listed on the service configuration which have been pushed out across the network.

Only one Service configuration per domain. E.g : www.yourSite.com can I have only one Service Configuration.

Subdomains and wildcards

Each subdomain should have his own service configuration, but It’s still possible to apply the same service config to all subdomains if you register a wild card. E.g : *.api.yoursite.com

Hosts

Hosts or also referred to as origin, it’s possible to add either a domain or an IP address.

Host is TLS and without

If you want to accept https, and non-https then you need to create separate Hosts.

Shielding

You can enable shielding from the configuration page. In my case the PAR (Paris) POP is defined as a shield.

Load Balancing

A load balancer is used to distribute work evenly among several backends. You can enable this option here.

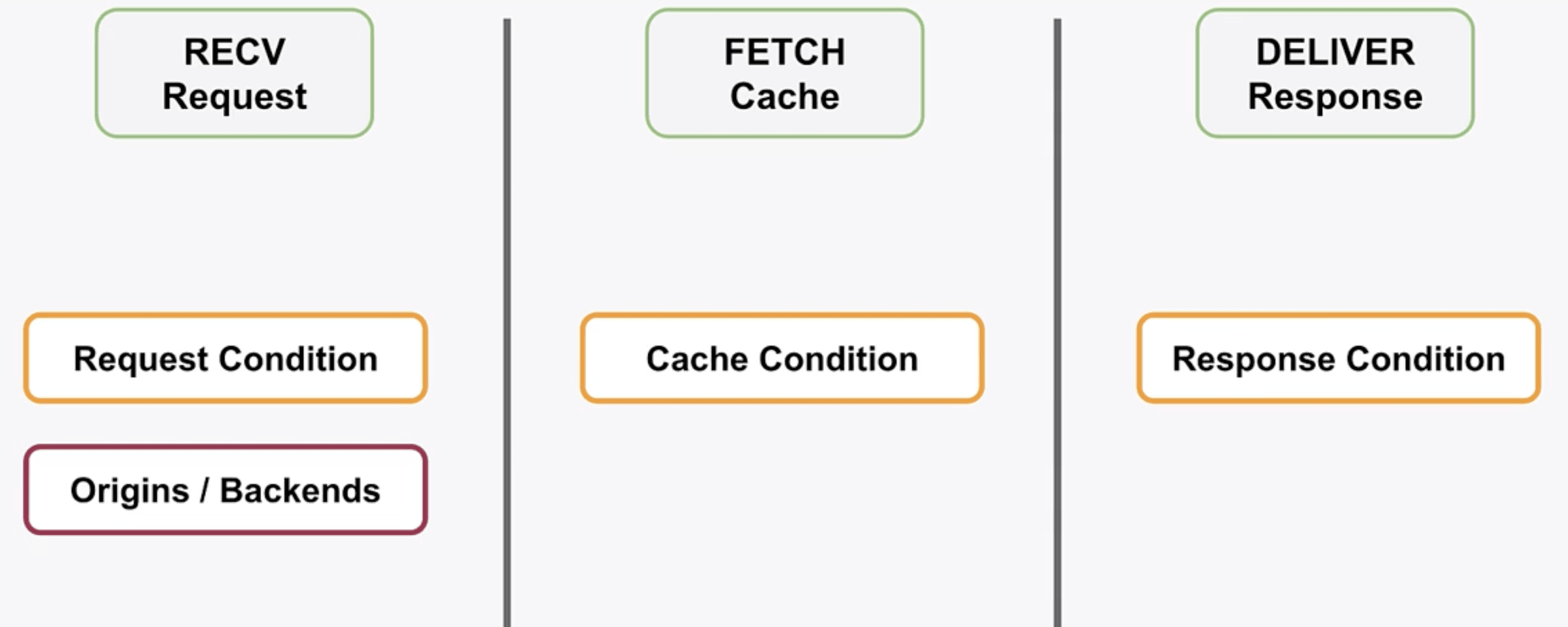

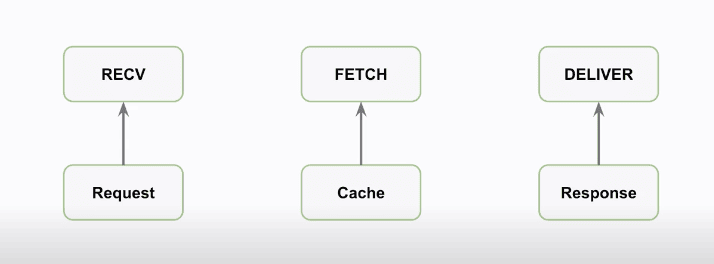

Linking Logic

Here we have our subroutines and their types :

RECV : Request

FETCH : Cache

DELIVER : Response

Between RECV and FETCH

It’s where maybe we don’t have the object in cache, and where we make the request to the backend. After we get the object back we run FETCH

Between FETCH and DELIVER

It’s where we decide to cache or not the object we received from the backend then DELIVER runs.

What happens within RECV

In RECV we can decide to switch from one backend to another if we want. Our logic is based on conditions, in our condition we can use different parameters like Settings, Content, Data.

Conditions within the subroutines

With the different subroutines, I can write a logic to:

- Decide where to run the request based on request conditions in RECV.

- Decide to cache and fetch from the cache based on cache conditions in FETCH.

- Decide to alter the response based on the response in DELIVER.

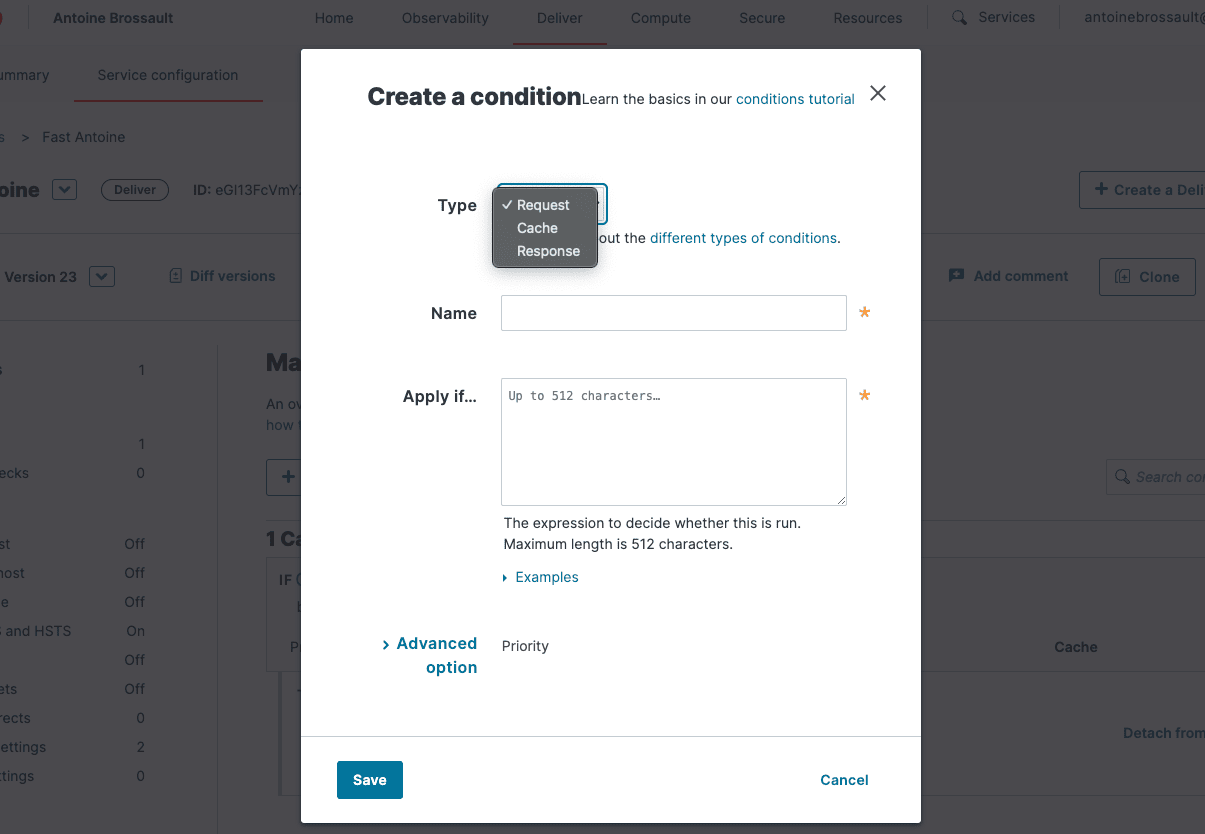

Conditions

How to create a condition on the UI

To set up a condition in the Fastly UI, follow these steps:

- Go to your service configuration and clone it.

- Next, navigate to the left sidebar and click on « Conditions. »

- Then, click on « Create condition. »

After you create a condition, you have to create a setting

How to create a setting in the UI

To create settings in the Fastly UI:

Settings

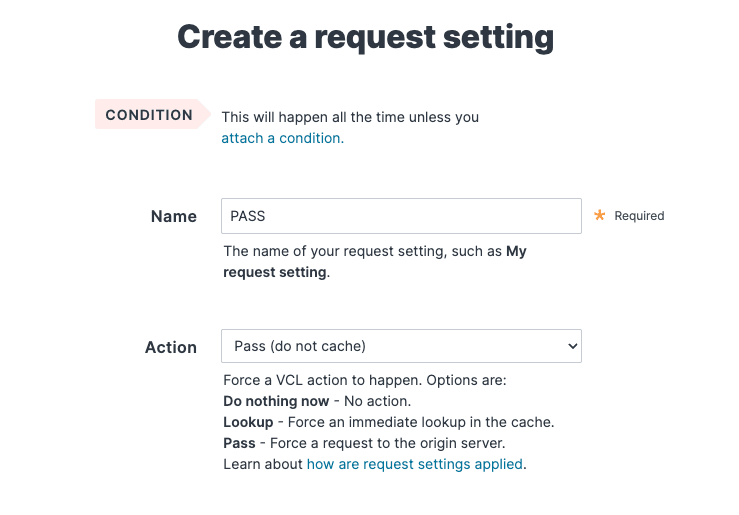

Request setting

Go to « Settings. »

Scroll down until you find « Request Settings » or « Cache Settings. »

In « Request Settings, » you determine how to handle the request without modifying it.

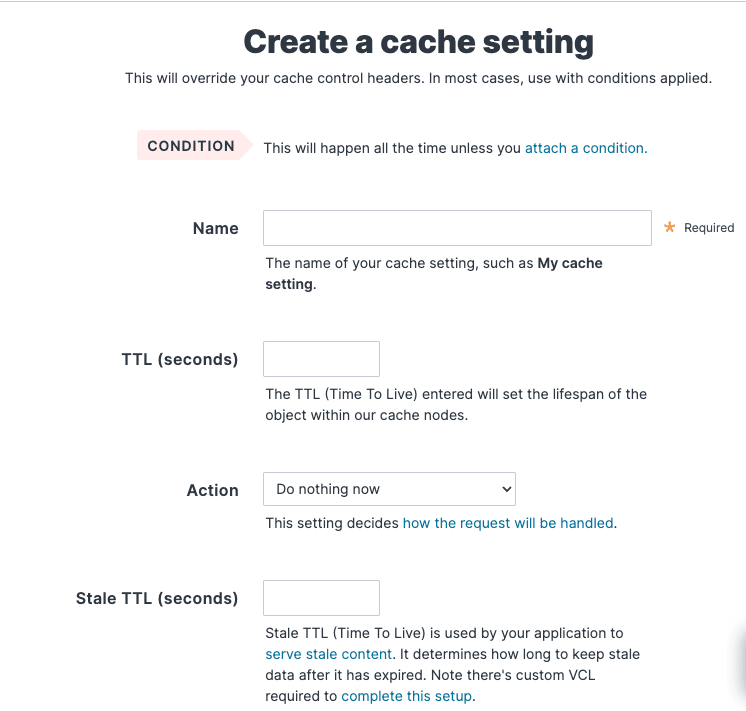

In « Cache Settings, » you decide whether to cache, pass, or perform other actions.

In my request settings, I’ve simply set it to « PASS, » which means the request won’t be cached.

Cache setting

Example : how to exclude API calls from cache

In this video, I’ll demonstrate how to set up a request condition to match all requests containing /api and then apply a cache setting to prevent caching those requests.

Note that it can take a couple of minutes for the changes to take effect on your app.

Header setting : How to set or rewrite headers ?

Response setting : A custom 404

Another helpful synthetic response could be to set up a redirect. It’s worth noting that you can customize the response status as well.

Takeaways

• Setting types are linked to certain VCL Subroutines

– Request -> Recv

– Cache -> Fetch

– Response -> Deliver

• Using the Ul, you can build configuration setting using:

– Conditions

– Setting

– Content (settings)

– Data (structures)

• Data can be referenced in the logic of your Conditions.

• Snippets are code blocks that can be included in any subroutine.

• Snippets can be Regular (Versioned) or Dynamic (Versionless).

• Custom VCL allows for behaviors that require code blocks in multiple

VCL states :

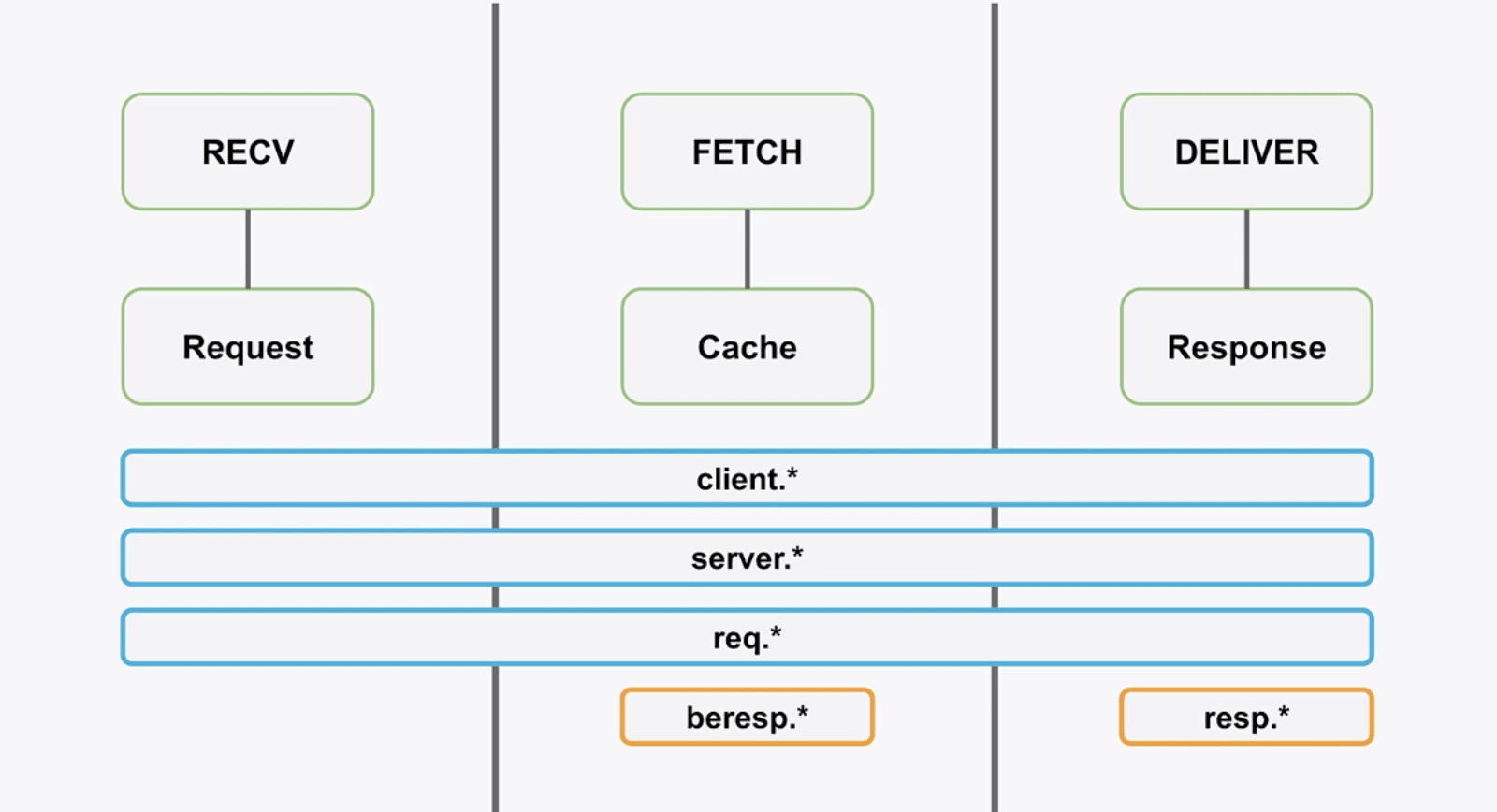

This article zooms into the steps of dealing with requests using Varnish, shown in a diagram. We’ll mainly look at three important parts: RECV, FETCH, and DELIVER.

RECV, FETCH, and DELIVER.

RECV :

We refer it as a request type, used when we receive the request.

In this condition we have access to the following variables ( to me they are more like objects )

client.*

server.*

reg.*

FETCH :

We refer it as a cache type, used when we cache the request

client.*

server.*

reg.*

resp.*

beresp.* stands for « Back-end response »

DELIVER:

We refer it as a response type, used when we modify the response before sending it to the end user.

client.*

server.*

reg.*

resp.*

resp.* is for the response we send back to users.

Examples of what we can access :

client.ip

client.port

client.requests

server.datacenter

server.ip

Server.port

Req.url

Req.host

req.http.*

VLC methods and subroutines

RECV runs after the Delivery Node gets a request.

FETCH runs after we get a backend response & before we cache the object.

DELIVER runs before we send the response to the end user.

Takeaways

• Using the Ul allows you to add logic and configurations into the RECV, FETCH, & DELIVER subroutines.

• RECV runs after the Delivery Node gets a request.

• FETCH runs after we get a backend response & before we cache the object.

• DELIVER runs before we send the response to the end user.

• Logic and configs in the Ul fall into three types: Request – Cache – Response

• Each of the above three type has different variables available to reference.

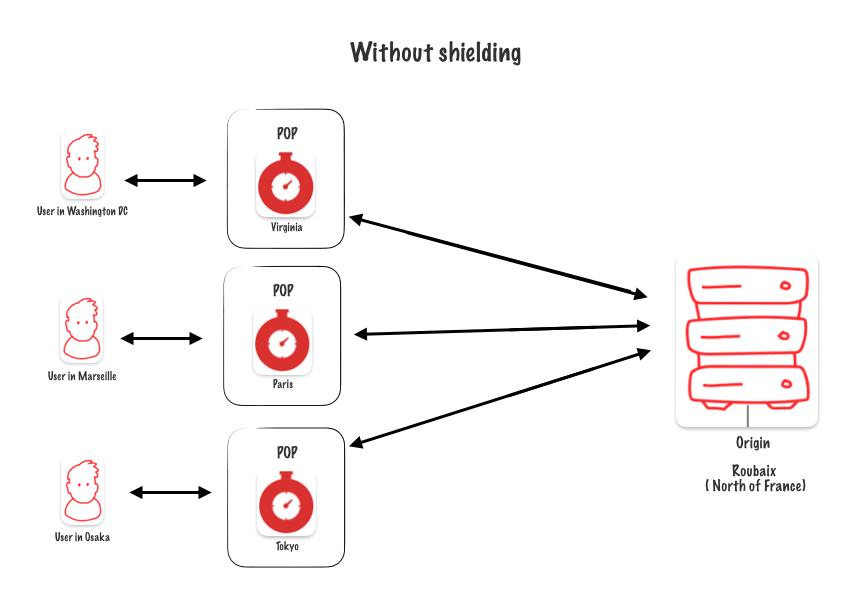

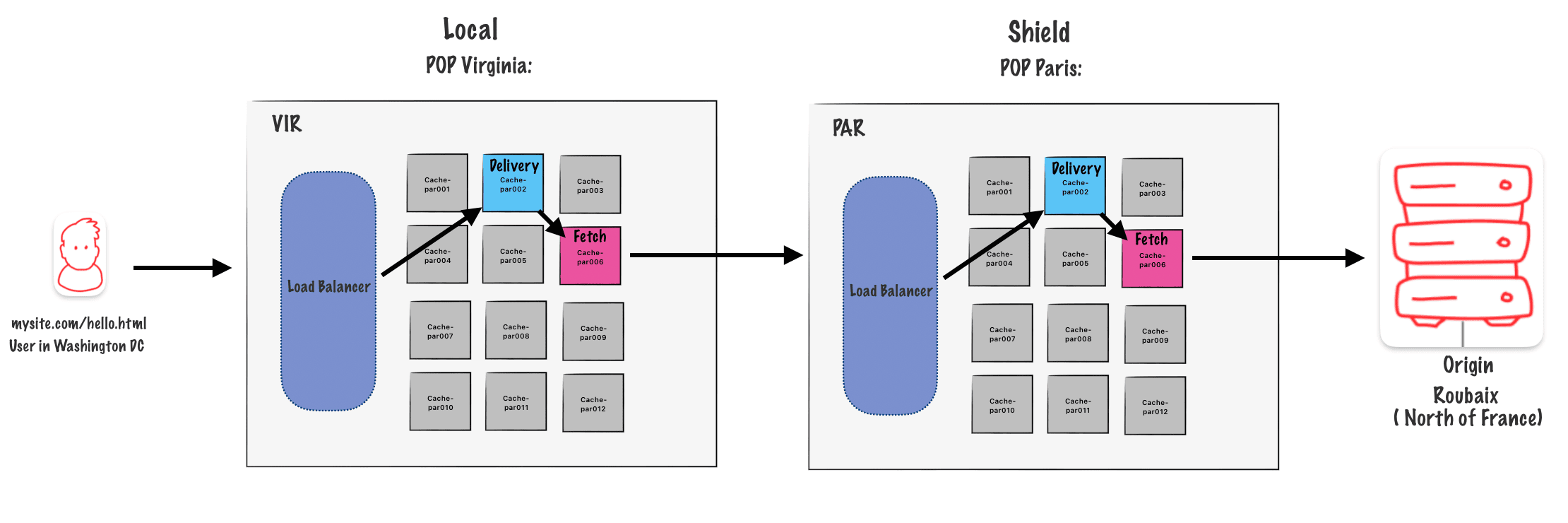

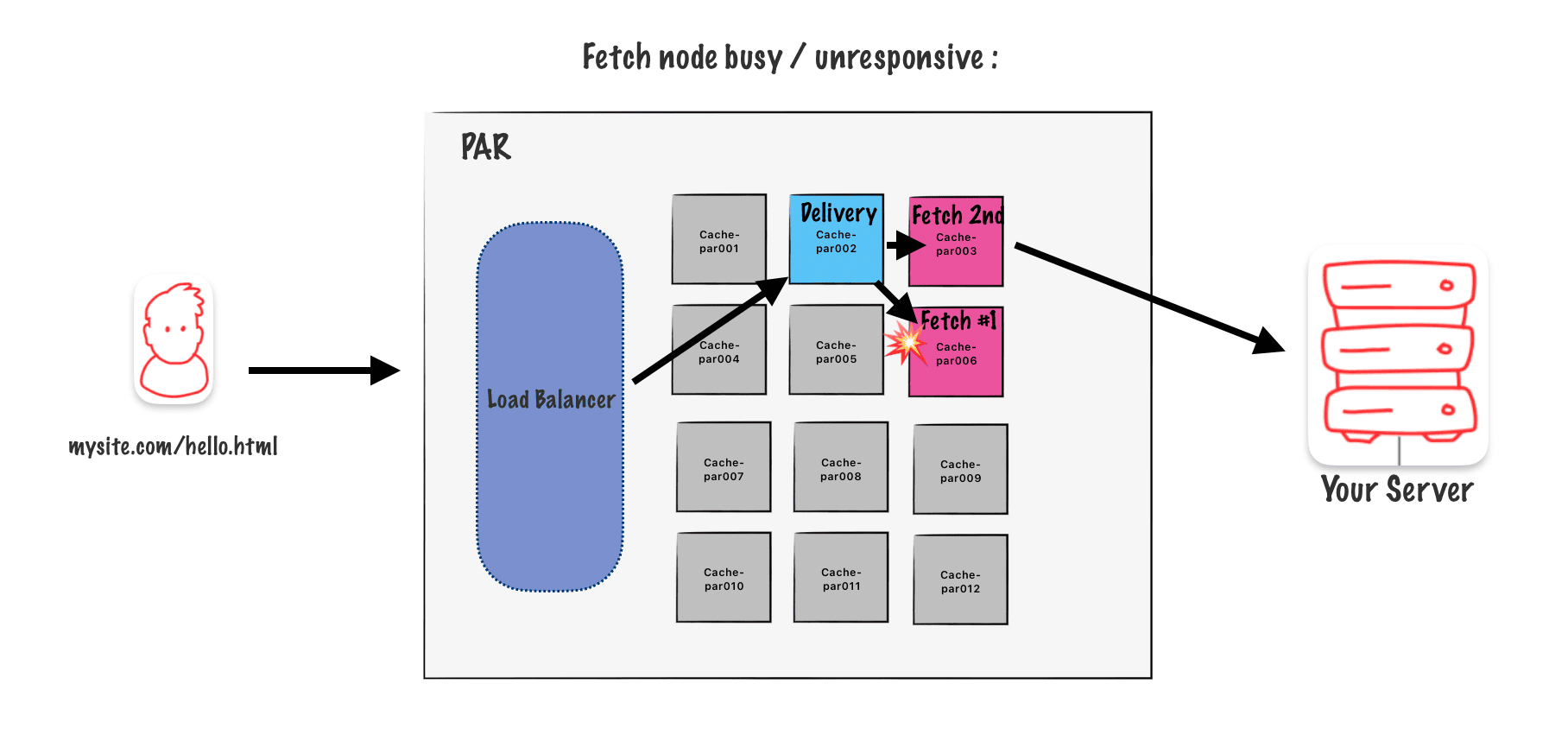

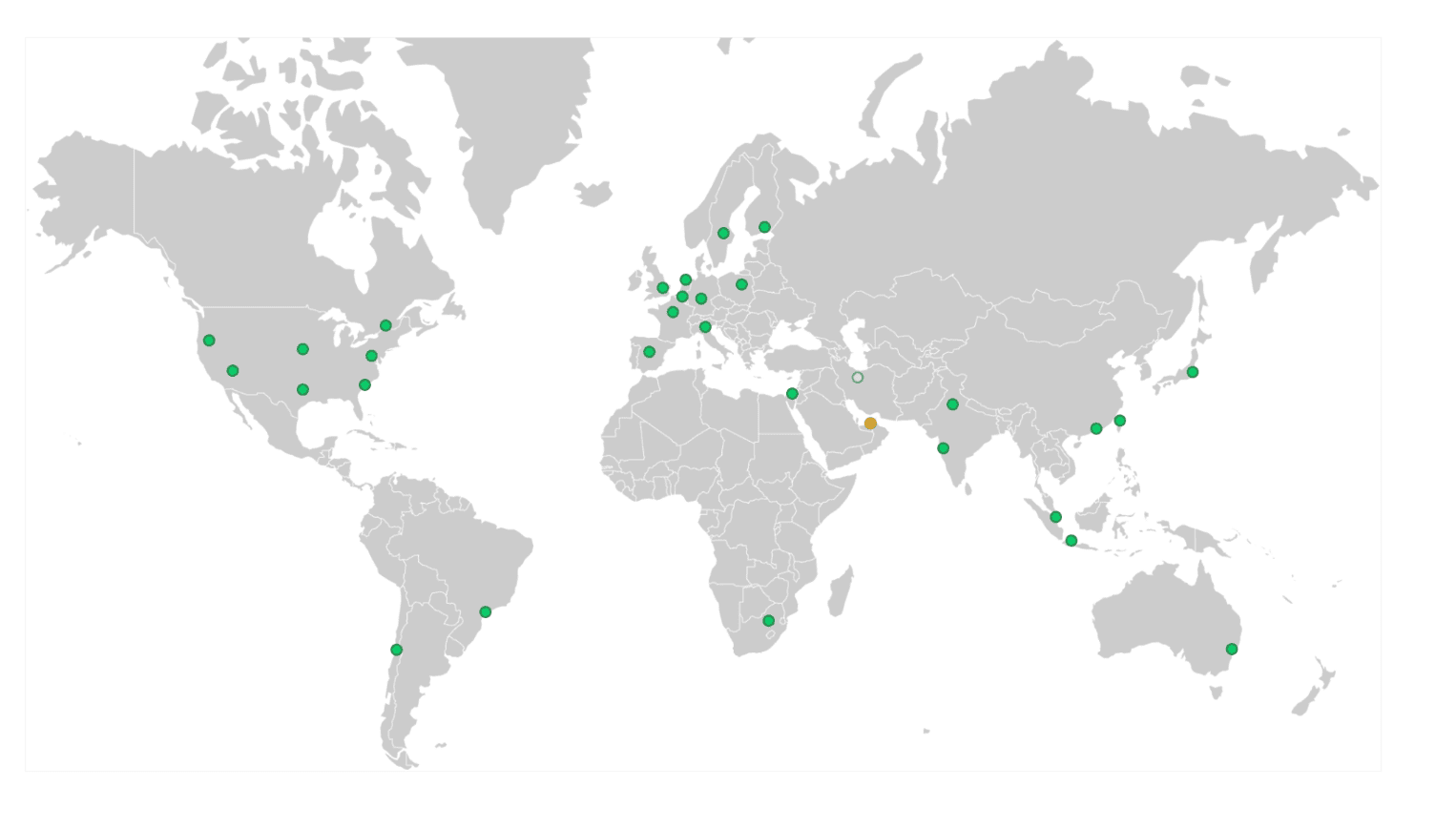

Without shielding

To understand shielding, let’s look at this diagram. My main server is in Roubaix, France. My aim is to lighten the load on this server as much as possible.

Requests come from all over the world, handled by the nearest Fastly POPs. However, these POPs still need to reach my server to refresh the cache, creating inefficiency as every POP accesses my origin.

To improve this, we can place a cache server between the POPs and my origin. This server, acting as a shield, absorbs requests and delivers cached content, reducing the direct load on my origin server and improving efficiency.

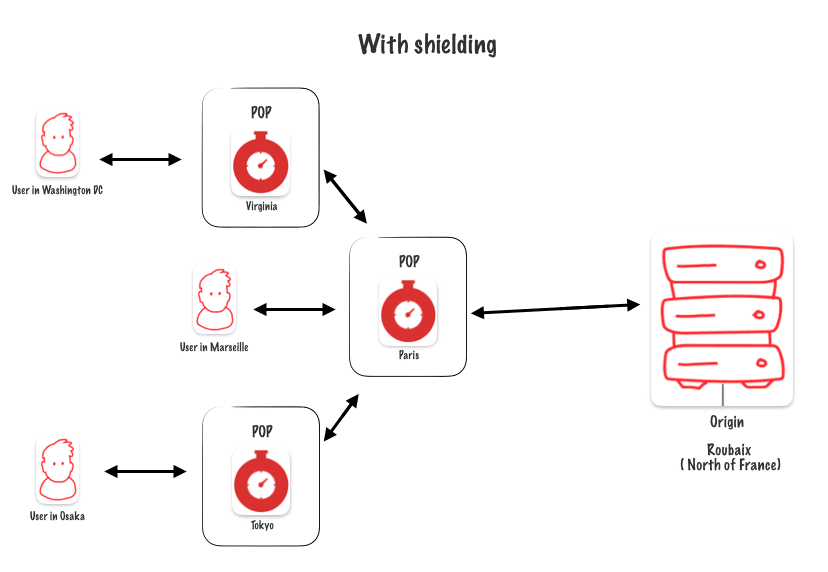

With Shielding

The Paris POP acts as an additional caching layer. Since it’s closest to our origin, it will handle all the load from other POPs when they need to access my origin server.

Multiple shields

You can set up multiple shields if you have multiple origins. Just like before, keep your shields close to your origins for better efficiency.

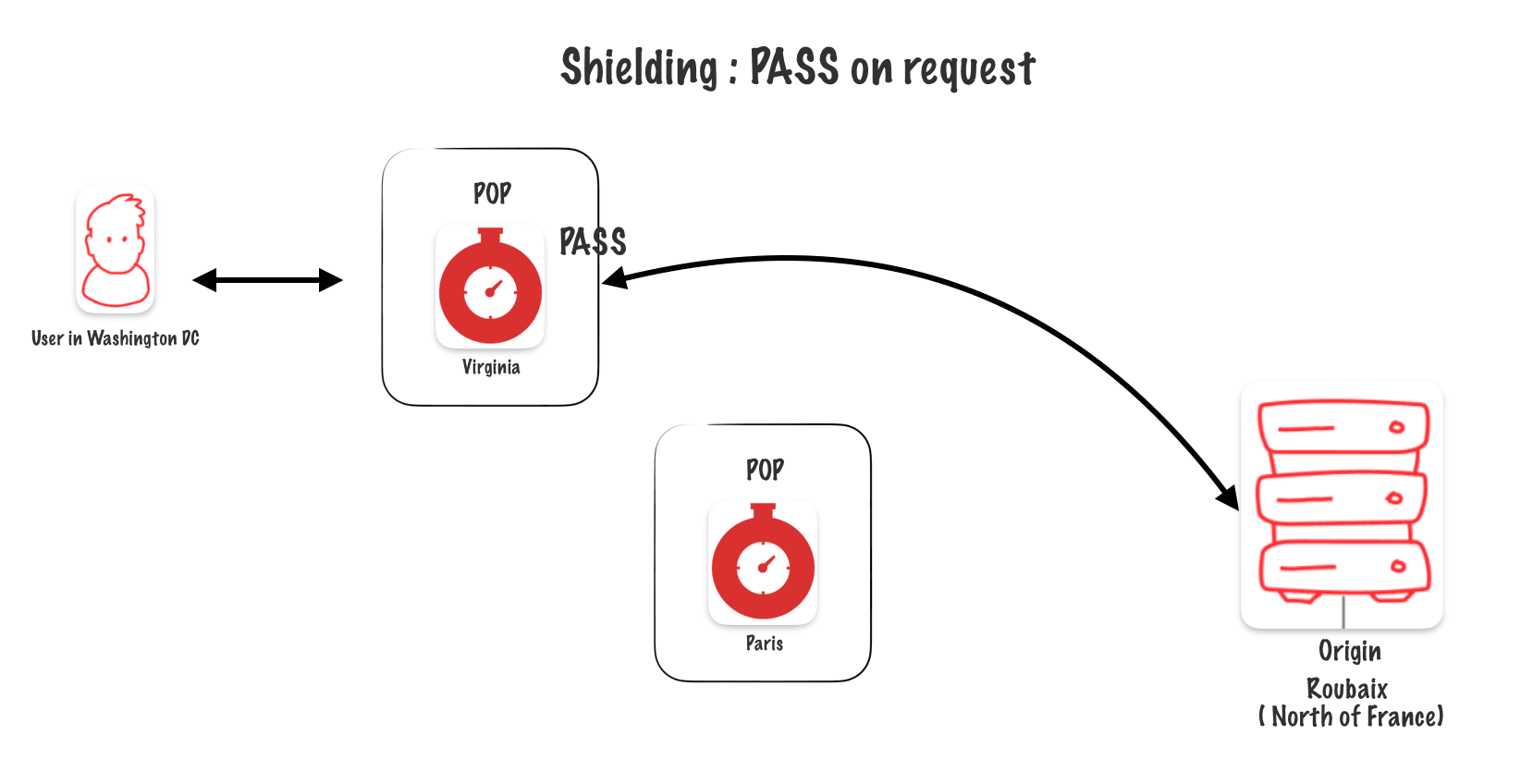

Skipping the shield with PASS on the request

If « PASS » is called on the request, it skips the shields and goes directly to the origin.

Shielding adds another caching layer

Since the shield is essentially an extra POP, you gain benefits from POP features like clustering, which adds another layer of caching.

How to visualize your shield?

Run the following command

curl -I -H "Fastly-Debug: 1" https://www.antoinebrossault.com

Then observe the fastly-debug-path :

For that example I ran the command from a german IP

fastly-debug-path:

(D cache-fra-etou8220158-FRA 1740688295) (F cache-fra-etou8220129-FRA 1740688295)

(D cache-par-lfpb1150066-PAR 1740688295) (F cache-par-lfpb1150066-PAR 1740637340)

We read the values from left to right.

Here the edge pop ( the first one to process our request ) is cache-fra-etou8220158

and the shield is cache-par-lfpb1150066-PAR

Note: fra stands for Frankfurt and par stands for Paris.

We can also see the details of the machines used for the delivery (D) node and the fetching (F) node.

Edge pop (Frankfurt): 🇩🇪

(D cache-fra-etou8220158-FRA 1740688295) (F cache-fra-etou8220129-FRA 1740688295)

And our shield (Paris) : 🇫🇷

(D cache-par-lfpb1150066-PAR 1740688295) (F cache-par-lfpb1150066-PAR 1740637340)

How to interpret x-cache and x-served-by values?

curl -I -H "Fastly-Debug: 1" https://www.antoinebrossault.com

HTTP/2 200

server: Apache/2.4.62 (Debian)

...

x-served-by: cache-par-lfpg1960059-PAR, cache-fra-etou8220027-FRA

x-cache: HIT, HIT

Here we have to read from right to left

edge pop is : cache-fra-etou8220027-FRA ( Frankfurt 🇩🇪 )

shield pop is : cache-par-lfpg1960059-PAR( Paris 🇫🇷 )

How to read x-cache: HIT, HIT

Here, the first HIT (reading from right to left) is the edge POP that had the request in cache in Frankfurt 🇩🇪

and previously (not that request) when it was a MISS on the edge in Frankfurt 🇩🇪, that POP gotput in cache the resource from the shield

You can readme about this in the Fastly doc

An other example with a request in Australia

My site is shielded in Paris, and I decided to connect with a VPN that has an Australian IP address.

So the first time I access the page with my Australian IP the page was not in the cache in Sydney ( WSI ) 🇦🇺 we can see that with the curl command below

curl -I -H "Fastly-Debug: 1" https://www.antoinebrossault.com/blog/

HTTP/2 200

fastly-debug-path: (D cache-wsi-ysbk1060062-WSI 1753723606) (F cache-wsi-ysbk1060037-WSI 1753723606) (D cache-par-lfpg1960038-PAR 1753723606) (F cache-par-lfpg1960038-PAR 1752726591)

fastly-debug-ttl: (M cache-wsi-ysbk1060062-WSI - - 997015) (H cache-par-lfpg1960038-PAR 30538985.291 43200.000 997015)

fastly-debug-digest: faf4bdf346bfe0fe44a8db4ffd1e461422957e17f2a2cd45a8bd247ecc993474

x-served-by: cache-par-lfpg1960038-PAR, cache-wsi-ysbk1060062-WSI

x-cache: HIT, MISS

If we observe the values of x-served-by below, we can see we went to the Sydney POP (WSI) 🇦🇺 first, then to the shield in Paris (PAR) 🇫🇷

x-served-by: cache-par-lfpg1960038-PAR 🇫🇷 , cache-wsi-ysbk1060062-WSI 🇦🇺

Again we read from right to left :

If we observe the values of x-cache below, we can see the resource was not in the cache in the Sydney POP (WSI) 🇦🇺 first, but it was in the cache in the shield in Paris (PAR) 🇫🇷

x-cache: HIT 🇫🇷 , MISS 🇦🇺

Then the second time I access the page with my Australian IP

This time the page was in cache in the cache in Sydney ( WSI ) 🇦🇺 as we have a hit in the x-cache: HIT 🇫🇷, HIT 🇦🇺

curl -I -H "Fastly-Debug: 1" https://www.antoinebrossault.com/blog/

HTTP/2 200

fastly-debug-path: (D cache-wsi-ysbk1060051-WSI 1753723623) (F cache-wsi-ysbk1060037-WSI 1753723606) (D cache-par-lfpg1960038-PAR 1753723606) (F cache-par-lfpg1960038-PAR 1752726591)

fastly-debug-ttl: (H cache-wsi-ysbk1060051-WSI - - 997032) (H cache-par-lfpg1960038-PAR 30538985.291 43200.000 997015)

fastly-debug-digest: faf4bdf346bfe0fe44a8db4ffd1e461422957e17f2a2cd45a8bd247ecc993474

x-served-by: cache-par-lfpg1960038-PAR, cache-wsi-ysbk1060051-WSI

x-cache: HIT, HIT

Takeaways

• The free Shielding feature allows a single POP to act as an additional caching layer

between the user and the origin.

• Each backend configuration can have a different POP selected as it’s Shield POP.

• This allows different Shields to be configured, one per

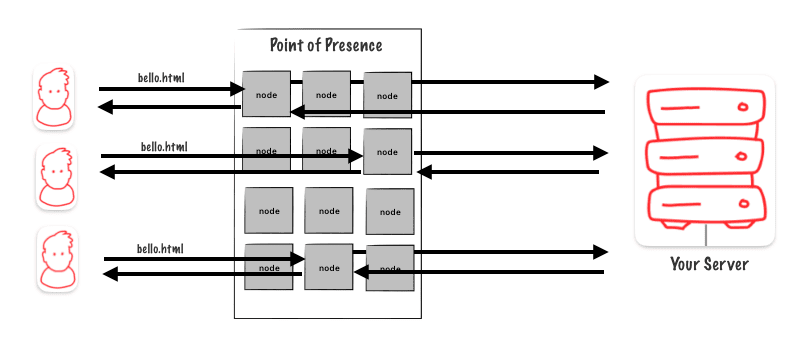

The clustering nodes

In a Point of Presence (PoP), there are several nodes that work independently. Each node has its own hash table to keep track of cached objects. When a user sends a request, if the node handling the request doesn’t have the requested object in its hash table, the request must go to the origin.

However, this process is inefficient because the chances of the node responsible for responding having the requested object in its cache are not high.

How can we make sure the origin server doesn’t get overloaded?

What we can do instead is create a single node responsible for making requests to the origin

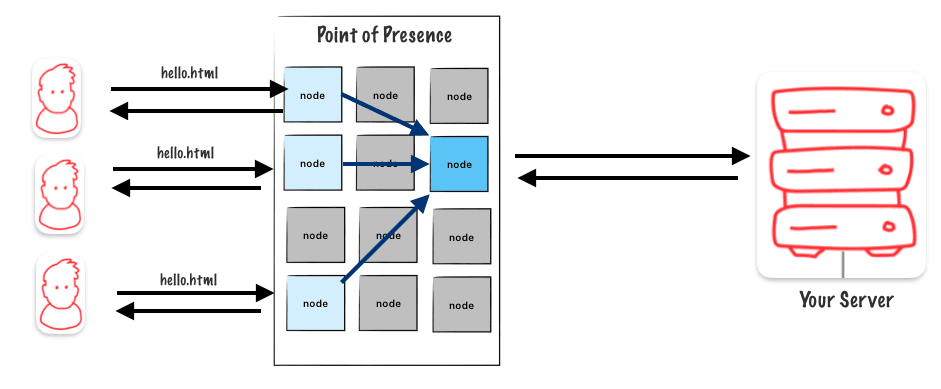

Designate a single node responsible for the object

In this example, there are three users asking for a file. Each user’s request is handled by a separate node. If the requested file isn’t in the cache of the node handling the request, that node will go to another designated node (the chosen one) to fetch the data from the origin.

Reminder on the hash keys and hash table

The parameters used to generate the hash key are:

- The host like :

fastly.antoinebrossault.com - The URL :

/hello - And a generation ID :

1– e.g : 1

Hash for fastly.antoinebrossault.com/hello = 21357f4e1d9a-13a7bc88b63d-1

Recap of the caching behavior regarding of the hashtable :

- A request with a difference in either the Host or the URL will generate a different Hash

Key. - A cacheable response object from a request will be cached with that Hash Key on the

Hash Table. - When another request comes in and generates the same Hash Key, we can check for the matching Hash Key on the Hash Table and can serve the cached response object.

- No key match on the table? It’s not cached, it’s a MISS, fetch it from the backend.

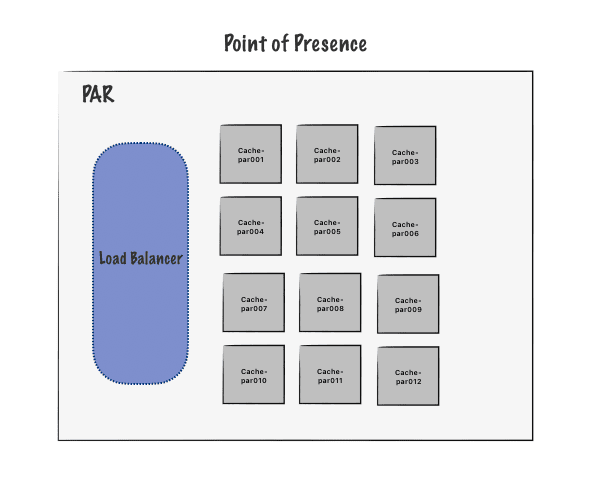

Anatomy of a Point Of Presence :

In a point of presence, there are many nodes. A load balancer in front of these nodes decides which one will handle each incoming request.

Delivering and Fetching node logic in a POP

Here’s a simplified overview of the logic in a POP:

- 1) Request hits the load balancer.

- 2) Load balancer selects a delivering node.

- 3) In the delivering node:

- Check if the request’s hash is in the hashtable.

- If yes, return the object from the node cache.

- If not, proceed to the fetching node.

- 4) In the fetching node:

- Check if the request’s hash is in the hashtable.

- If not, go to the origin.

- 5) After fetching from the origin:

- Populate the cache of the fetching node.

- Send the object back to the delivering node.

- The delivering node caches the object and updates its hashtable.

- 6) Finally, the delivering node sends back the data to the user.

Schema :

Here’s a schema of the logic in a POP, to be honest I wanted to make it simpler, and I ended up with a not 100% clean schema, so sorry about this….

In this schema the black arrows are going forwards when the blue dashed lines represent the request going back.

When Delivering and Fetching node behaviors are disabled

PASS & Restart disable clustering

PASS :

When a request has a « PASS » instruction, caching is unnecessary, so we turn off the clustering behavior.

Restart :

Restart is a way to handle errors from the origin. In this case, we don’t cache the origin response; instead, we return it directly to the user.

A secondary fetching node as a fallback

The usual behavior is as I described earlier, which is shown in this diagram.

But what if the fetching node gets too busy or stops responding? In that case, the delivery node can choose a backup secondary node automatically. This logic is built into the algorithm.

Takeaways

• Clustering is a set of Node behaviors within a POP, that improves caching performance and reduces request load to the origin.

• Nodes can fulfil both the Deliver Behavior and the Fetch Behavior.

• The request hash key is used via algorithm to determine the Primary Node for that request. The Primary then acts as the Fetch Node.

• The Primary, when acting as the Delivery Node, will use the Secondary Node as it’s

Fetch Node.

• When the Primary Node is down, the Secondary Node acts as the Fetch Node.

• Different Hash Key = Different Fetch

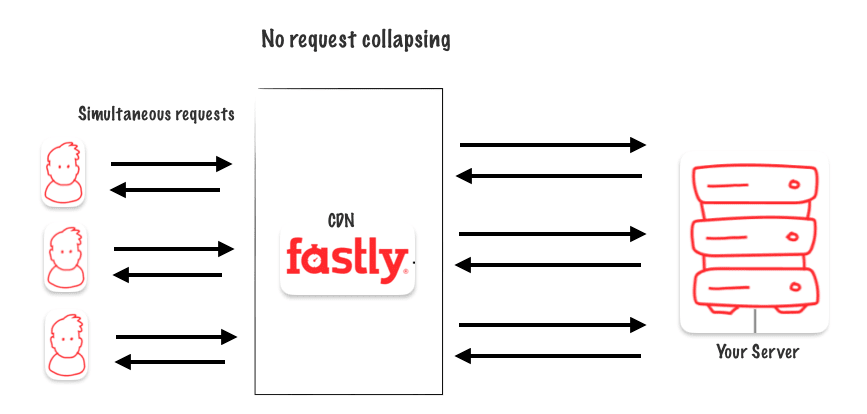

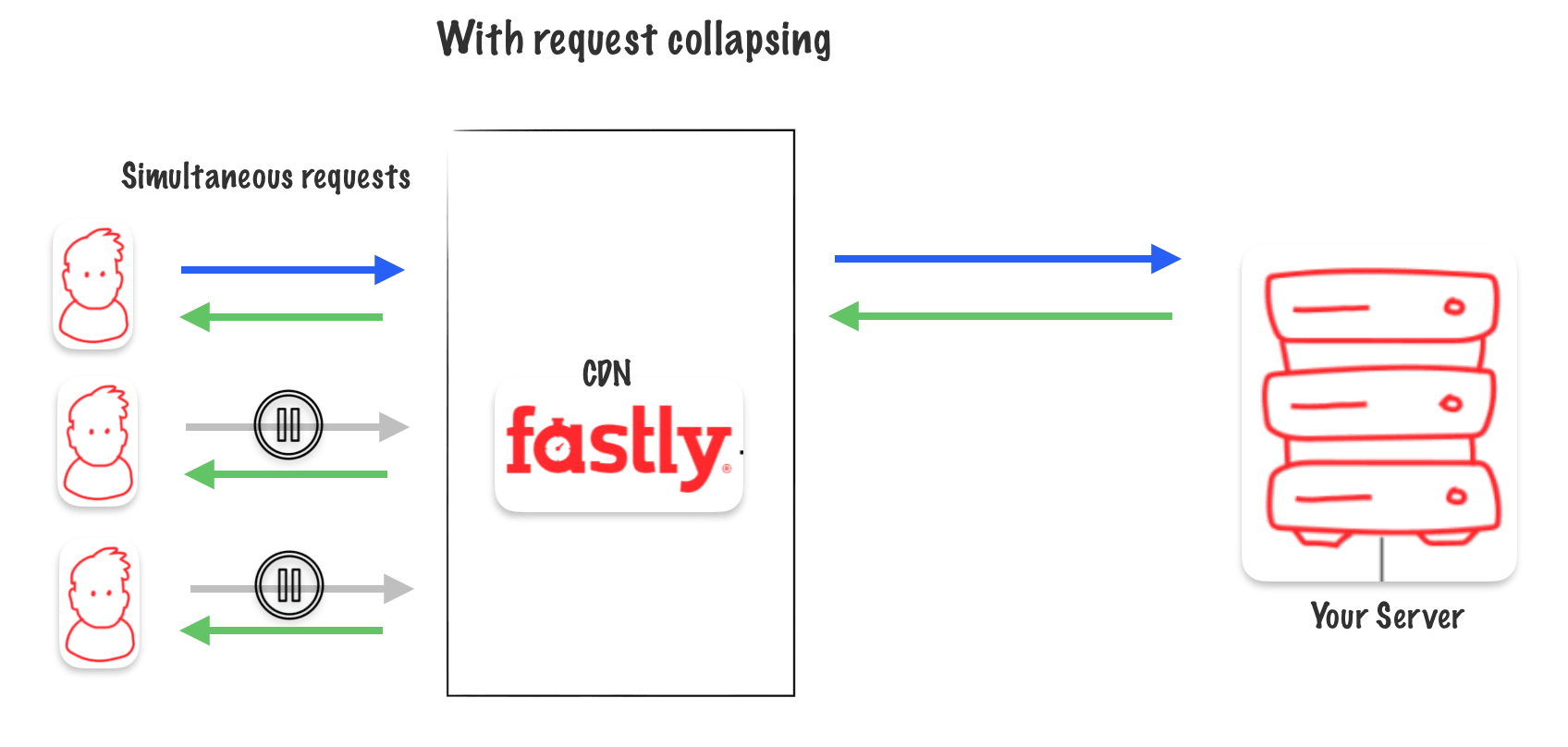

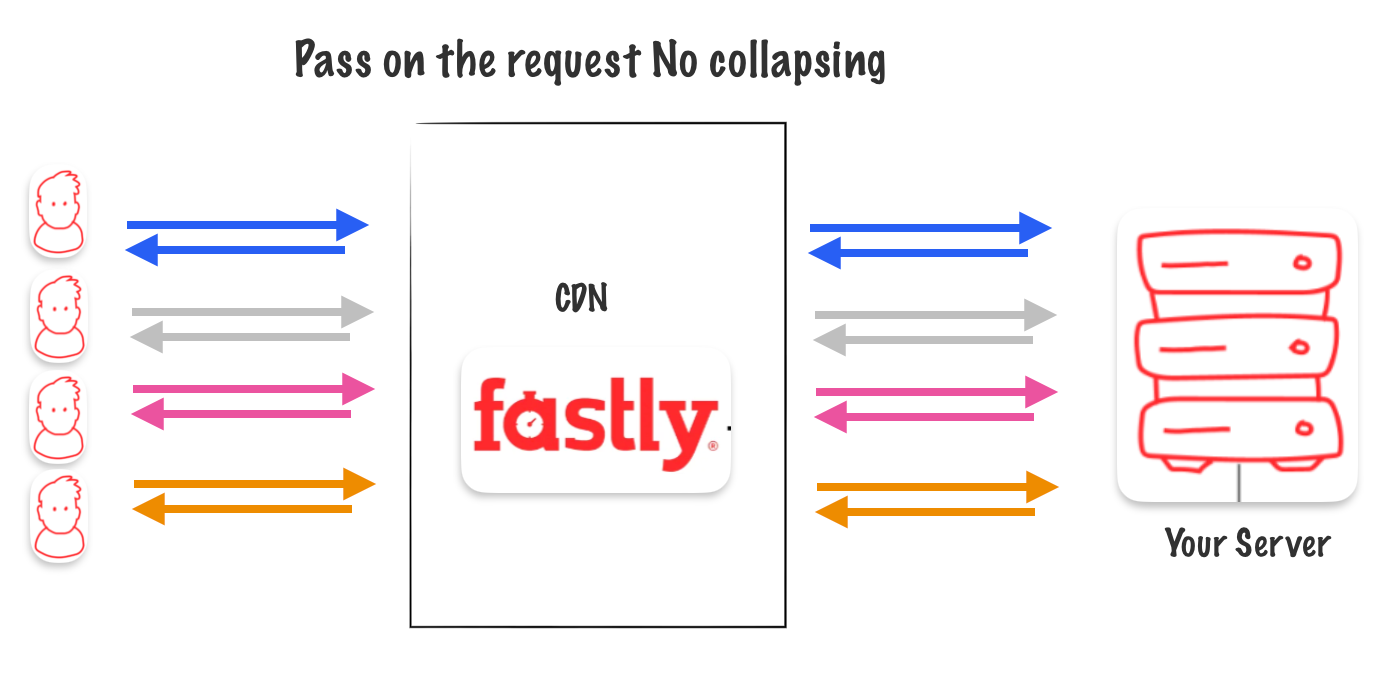

What’s request collapsing ?

Concept of request collapsing in the context of a cache system refers to the scenario where multiple identical requests for the same data are received by the cache system simultaneously or within a short period of time. Instead of processing each request separately, the cache system can collapse or combine these identical requests into a single request, thus reducing the load on the backend system and improving overall efficiency.

The goal is to guarantee that only one request for an object will go to origin, instead of many. With Faslty, Request Collapsing is enabled by default for GET/HEAD requests. It is disabled otherwise.

Request collapsing for a cacheable object

In request collapsing, when many requests come in at once, the system chooses one main request (called the « champion request ») to get the data from the original source and store it in the cache. Other requests are then paused until the cache is updated with the data. This helps manage the workload efficiently.

In request collapsing, when many requests come in at once, the system chooses one main request (called the « champion request ») to get the data from the original source and store it in the cache. Other requests are then paused until the cache is updated with the data. This helps manage the workload efficiently.

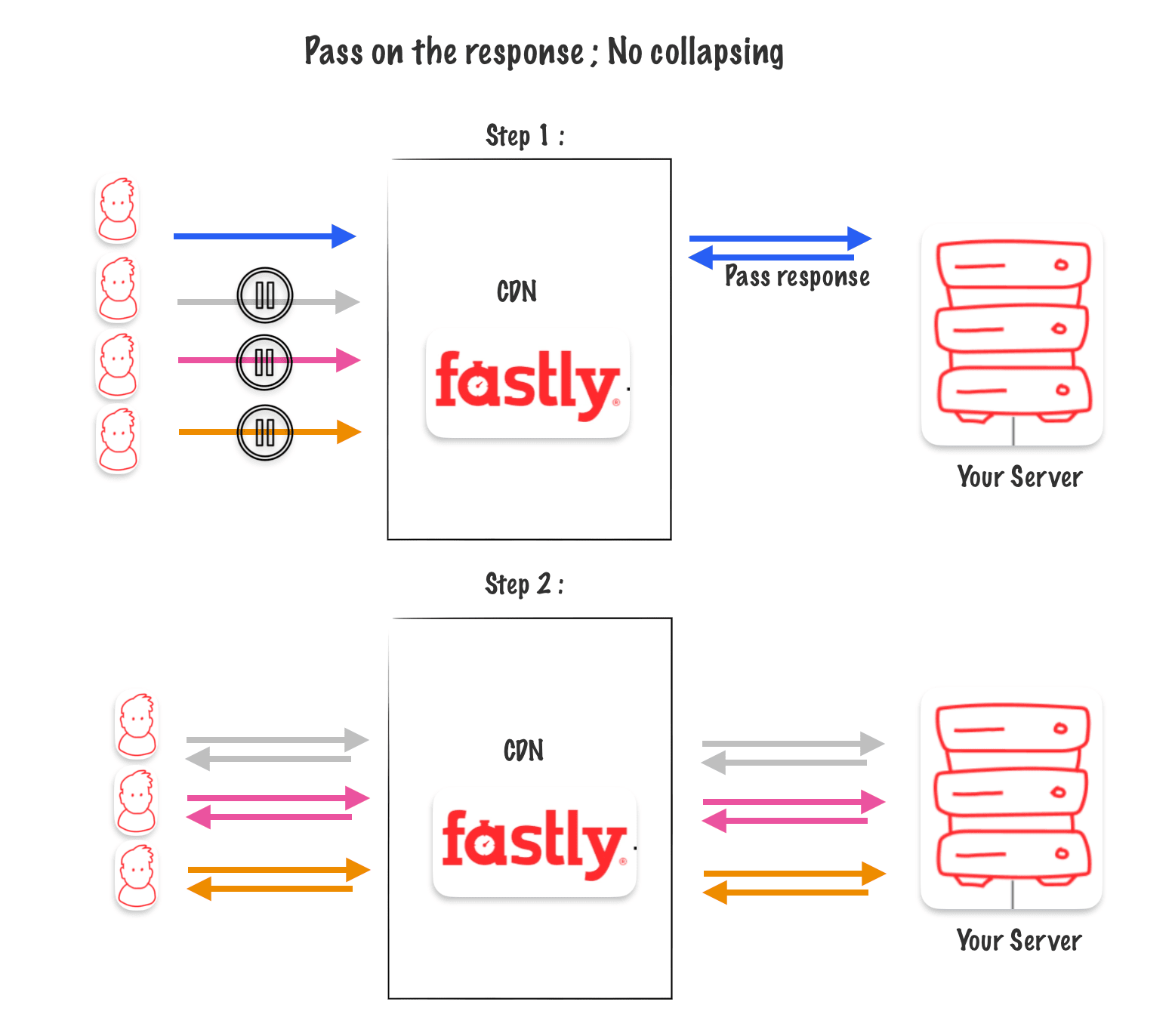

PASS Called on the request

You can change how the cache system works by turning off request collapsing for certain types of requests. When this happens, all requests are sent directly to the original source instead of being combined.

PASS Called on the response

If you choose to bypass the cache when responding (using a header or setting a cookie, for example), the waiting requests are reactivated after the first response. However, this method isn’t as efficient as bypassing the cache when requesting data because we have to wait for the response to receive the final instructions.

Hash key for pass on the reponse

When you pass on a response, the hash key for that request is marked with a « PASS » value for the next 120 seconds. This means that for the next 120 seconds, all requests with the same hash key will also pass through the cache.

Response object is not cacheable but no PASS

If neither a « PASS » is called on the request nor on the response, it’s possible to receive an uncacheable response from the origin.

For example, if your server crashes and sends back a 500 error. In this case, the champion request gets a 500 response, and then the next request is triggered. Hopefully, the second one receives a response from the origin that isn’t a 500 error.

Takeaways

- For Cacheable objects, Request Collapsing collapses many backend request into one.

- PASSing on the Request disables Request Collapsing.

- A non-cacheable response, will sequentially awaken requests to the backend.

- A PASSed Response, awakens all pending requests and sends them to the backend.

- A PASSed Response triggers a

Why purging ?

If you want to make sure everyone sees the latest version of something on a website, like a new headline, you might need to « purge » or clear out the old version from the cache. It’s like refreshing a page to see the newest updates. So, if you change the headline on a webpage and you want everyone to see the change immediately, you’ll need to purge the cached version. That way, when people visit the page again, they’ll see the updated headline right away.

Different ways to purge

With Fastly, you’ve got a couple of ways to purge content from the cache.

Single URL purge

One option is to purge a single URL. In simple terms, you just point to the URL you want to refresh, and it gets cleared out from the cache. The cool part? It happens super quick! (about 150 milliseconds)

Surrogate Key Purge

Another way to purge is by using something called a Surrogate Key Purge.

This method relies on surrogate keys, which are like tags attached to articles or media files. Using this technique, you can clear out all the URLs associated with a specific tag, category, or the URLs affected by recent changes you’ve made live.

Another neat thing about this approach is that you can purge multiple URLs in one go by purging using multiple surrogate keys.

Purge All

Another option is to purge everything, which means removing all cached items under a service configuration. However, this approach comes with a risk. If you get too many requests to your origin server all at once, it could overload your server, almost like a self-inflicted DDoS attack.

How the Hash key is used to purge-all

The parameters used to generate the hash key are:

The host like : fastly.antoinebrossault.com e.g : 21357f4e1d9a

The URL : /hello e.g : 13a7bc88b63d

And a generation ID : 1 - e.g : 1

Hash for fastly.antoinebrossault.com/hello = 21357f4e1d9a-13a7bc88b63d-1

When you execute a purge-all command, the generation number is incremented by one. As a result, for the subsequent request, the hash will be different, causing a cache miss.

For example, the previous hash could be 21357f4e1d9a-13a7bc88b63d-0, and after the purge, the hash becomes 21357f4e1d9a-13a7bc88b63d-1.

The crucial point to grasp is that a purge-all command doesn’t actually remove the object from the cache. Instead, it alters the hash associated with the object, effectively making it unreachable.

Soft Purge

Another way to purge content is by using a soft-purge method, where instead of rendering the object unreachable by altering the hash, you mark the object as stale. This means the object can still be accessed, even though it has been invalidated.

But when might you use this? Well, consider content where serving the absolute latest version isn’t crucial, such as a logo. In this case, the stale object can still be served for a specified period that you determine.

The available options for this method are:

- Stale-While-Revalidate

- Stale-if-error

Stale-While-Revalidate

Cache-Control: max-age=3600, stale-while-revalidate=3600

When a user visits the website to view a product page, the site fetches and caches the product details to ensure fast loading times for subsequent visitors. However, product information, such as pricing, availability, or reviews, may change frequently due to updates from suppliers or customer feedback.

In this scenario, the website implements the Stale-While-Revalidate strategy. When a user requests a product page, the cached version is served immediately, even if it’s slightly outdated (stale). At the same time, the server initiates a revalidation process to fetch the latest product information from the database or external sources.

Stale-if-error

Cache-Control: max-age=3600, stale-if-error=3600

When a user visits the news website to read an article, the server fetches and caches the HTML content of the article to ensure quick loading times for subsequent visitors. However, occasional server issues or network disruptions may result in temporary errors when attempting to fetch the latest version of an article.

In this scenario, the news website implements the Stale-if-error strategy. When a user requests to read an article, the cached version of the HTML page is served immediately. If the server encounters an error while trying to fetch the latest version of the article (e.g., due to server overload or database connection issues), the website continues to serve the cached version of the article HTML instead of displaying an error message to the user.

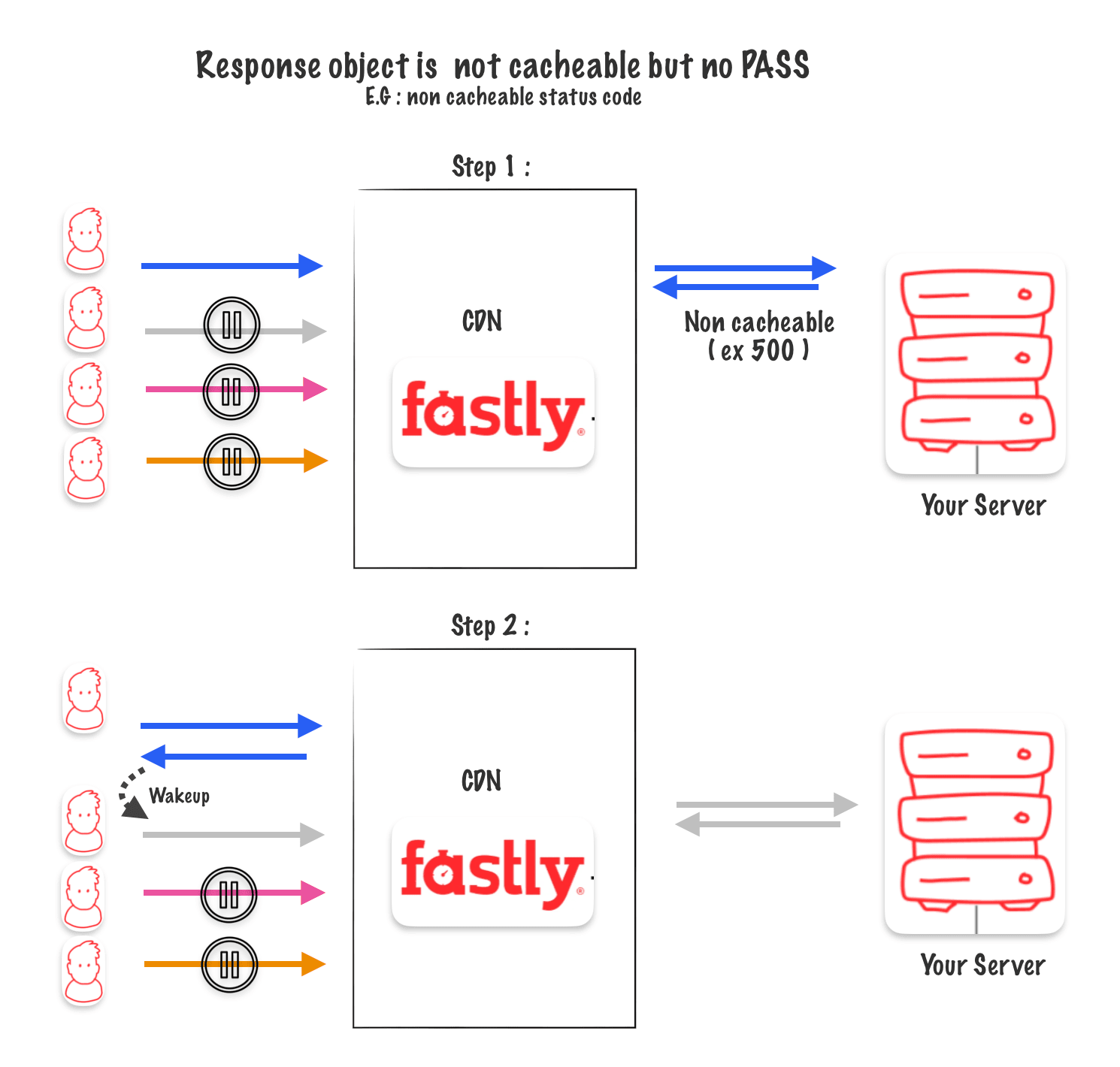

How to purge on Fastly ?

To perform a purge, you have several options available. You can use the user interface (UI), where you can either purge a single URL, purge by surrogate key, or initiate a purge-all operation.

Purge from the UI

Purge from the API

To purge content via the API, you can use the following call:

curl -X PURGE "https://fastly.antoinebrossault.com/"

As demonstrated in this video, the initial joke is served from the cache. By default, on the origin server, each HTTP call refreshes the joke. Here, I’m manually triggering a cache refresh using the API.

This call typically doesn’t require protection, but if desired, you can activate an option that requires an API key:

curl -X POST <url> -H "Fastly-Key:<Fastly APIKey>"

In the second call, replace <url> with the appropriate endpoint and <Fastly APIKey> with your Fastly API key.

Purge all

Here’s the code I use in my example app to run a purge all based on service :

const axios = require('axios');

require('dotenv').config()

const axiosConfig = {

headers: {

'Fastly-Key': process.env.FASTLYAPI,

'Accept': 'application/json'

}

};

exports.purgeAll = async (serviceID) => {

try {

const response = await axios.post(

`https://api.fastly.com/service/${serviceID}/purge_all`,

{},

axiosConfig

);

console.log('Purge request sent successfully:', response.data);

return response.data; // Return the response data if needed

} catch (error) {

console.error('Error purging all:', error.response.data);

throw error; // Re-throw the error if needed

}

}

Purge by Surrogate keys

curl -X POST -H "Fastly-Key:<Fastly API Key>"

https://api.fastly.com/service/<service_D>/purge/-H

'Surrogate-Key: key_1 key_2 key_3 key_4'

Options to authorize purge

Conditionally block purge calls by:

- Require Fastly Auth (key)

- Allowlist or Blocklist IPs

- Block via Geolocation

Limits on Purging

Purge by Service

Purges are limited by Service, so any content on different services will require separate purges.

Purge-All is Rate Limited

Authenticated users API calls are rate-limited to 1000 per hour.

Tokens

Account Tokens can limit the scope of purge privileges to:

- Account

- Service

- Purge type

What’s caching ?

In a web application, caching works like a high-speed memory that stores frequently accessed data or content. When a user requests information from the application, instead of fetching it from the original source every time, the application checks if it’s already stored in the cache. If it is, the data is retrieved quickly from the cache, significantly reducing the time needed to load the page or fulfill the request. This enhances the application’s speed and responsiveness, ultimately providing a smoother user experience.

Cache Terminology Explained

Understanding key terms like HIT, MISS, and PASS is essential to grasp how caching systems operate:

HIT:

When a requested object is found in the cache, it results in a HIT. In simpler terms, this means the cache already has the data stored and can swiftly deliver it to the user, bypassing the need to retrieve it from the original source.

MISS:

Conversely, a MISS occurs when the requested object is not present in the cache. In this scenario, the caching system must retrieve the object from the origin server, leading to slightly longer response times. Objects that consistently result in MISSes may be deemed uncacheable due to their dynamic or infrequent nature.

PASS:

In certain cases, Fastly (or any caching system) may opt to bypass caching altogether for specific objects. When an object is marked for PASS, Fastly will always fetch it directly from the origin server, without attempting to store it in the cache. This ensures that the freshest version of the object is always delivered to the user, albeit at the cost of caching benefits.

Cache Metrics: Understanding Cache Hit Ratio and Cache Coverage

Cache Hit Ratio

Cache Hit Ratio: It’s the proportion of requests successfully served from the cache compared to the total requests, calculated as the number of cache hits divided by the sum of cache hits and misses. A higher ratio indicates more efficient cache usage, while a lower ratio suggests room for improvement in caching effectiveness.

HIT / (HIT + MISS)

Cache Coverage

Cache Coverage: This metric assesses the extent of the cache’s utilization by considering the total number of requests that either resulted in a cache hit or miss, divided by the sum of all requests, including those passed through without caching. In simpler terms, it measures how much of the overall workload is handled by the cache, indicating its effectiveness in caching content. A higher cache coverage implies a larger portion of requests being managed by the cache, thus maximizing its impact on performance optimization.

(HIT + MISS) / ( HIT + MISS + PASS )

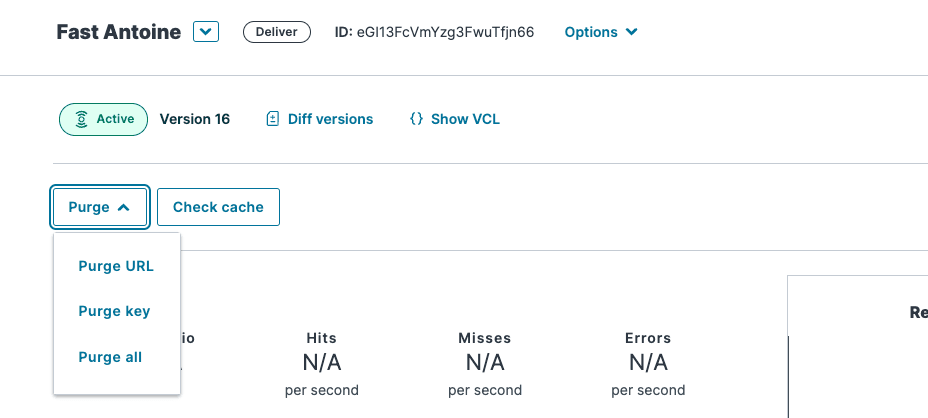

How to check if a response came from the cache ?

To find out if a request hit or missed the cache, just check the response header. For instance, in my example, if the « x-cache » key shows « HIT, » it means the response was fetched from the cache.

Manage the cache duration

The cache duration is calculated by Time-To-Live (TTL).

The TTL is not a header, but you can compute the TTL based on the headers used.

The Age header keeps increasing (you can see it in the gif). When the Age header’s value becomes greater than the TTL, it means the cache expires and gets invalidated.

How to keep track on the objects stored in the cache ?

How does a CDN like Fastly keep track of what’s in the cache? Well, on each node (and there are multiple nodes on a POP – Point of Presence), there’s a hash table that does the job.

This hash table generates a key for every request, using the host and URL. Whenever a response is cacheable, it’s added to this table. So, if you’re looking for something in the cache and it’s not in this table, it means it’s not in the cache.

So the host and URL are hashed like this :

{

"5678ab57f5aaad6c57ea5f0f0c49149976ed8d364108459f7b9c5fb6de3853d6" : "somewhere/in/the/cache.html"

}

How to use headers to control the cache :

You’ve got various headers to control caching in your response, determining whether to cache it and for how long.

Cache-Control:

This header is respected by all caches, including browsers. Here are some Cache-Control values you can use:

To explain clearly, those headers : Imagine your web server is a store and your visitors are customers. You can give instructions on how fresh their groceries need to be. Here’s how to do that with headers:

Cache-Control: s-maxage=

Cache-Control: max-age= (seconds): This is like saying « keep these groceries fresh for X seconds. » Browsers will use the stored version for that long before checking for a new one.

Cache-Control: max-age=

Cache-Control: s-maxage= (seconds): This is for special big warehouses (shared caches) that store groceries for many stores. It tells those warehouses how long to keep things fresh, overriding the regular max-age for them.

Cache-Control: private: This is like saying « these groceries are for this

Cache-Control: private

This is like saying « these groceries are for this customer only, don’t share them with others. » Browsers will store them but not share them with other websites you visit.

Cache-Control: no-cache

This is like saying « don’t store these groceries at all, always check for fresh ones. » Browsers will never store this type of item.

Cache-Control: no-store

This is stricter than nocache. It’s like saying « don’t even keep a shopping list for these groceries, always get new ones. » Browsers won’t store anything related to this item.

Surrogate-Control:

Another header you can use to control the cache is the Surrogate-Control.

This header is respected by caching servers but not browsers.

The values you can set for Surrogate-Control include:

max-age= (seconds)

Server will use the stored version for that long before checking for a new one.

Expires

Expires is a header that any cache, including browsers, respects. It’s only utilized if neither « Cache-Control »

« Surrogate-Control » headers are present in the response. An example of the « Expires » header would be:

Expires: Wed, 21 Oct 2026 07:28:00 GMT

This indicates that the cached response will expire on the specified date and time.

How to not cache (PASS) ?